William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare23 April 1564, 8:30am*

Stratford-Upon-Avon, England

Placidus Houses, True Node

Geocentric, Tropical

*Baptism (Source Notes)

Portrait of William Shakespeare,

possibly by John Taylor

When the topic of Shakespeare and astrology arises, generally people rummage around in his plays looking at various characters’ speeches to determine Shakespeare’s attitude to or “belief” in astrology. Favourites are Ulysses’ paean to order in Troilus and Cressida or, in contrast, Edmund the Bastard’s refutation of any stellar influence at his birth in King Lear. But the astrological model provides a much grander underlying archetypal structure for many of his plays. This paper brings together great literature, esoteric thought, and spiritual philosophy to show that astrological symbolism remarkably provides secret keys to unlocking deeper meanings in—to use one play as an example—Romeo and Juliet.

(In a second paper, I’ve explored the grand model of the cosmos from ancient times, certainly from classical Greece and even earlier from Egypt and Persia, and its path into Elizabethan times.)

Obviously Shakespeare is well acquainted with planetary archetypes because he often explicitly connects planets to particular characters. Sometimes the characters themselves announce their resonances with a particular planet. In Much Ado About Nothing, Sir John the Bastard allows that both he and Conrade, his companion, are "born under Saturn . . . I cannot hide what I am: I must be sad when I have cause, and smile at no man's jests . . . " (I, iii, 9-13) In The Winter's Tale, Autolycus (a thief) says of himself, "My father named me Autolycus; who being, as I am, littered under Mercury, was likewise a snapper-up of unconsidered trifles." (Iv, iii, 24-6) Mercury is a sly fellow; in Greek mythology, his first act after being born was to steal Apollo's cattle!

Similarly, Shakespeare uses characters' names to proclaim their archetypal identity, such as the Mars-type Hotspur who describes himself after warfare as "dry with rage and extreme toil" (Henry IV Part I, I, iii, 31) Another typical Mars-like character is "the fiery" Tybalt (as Benvolio dubs him--I, i, 116) who is always picking fights every time he appears in Romeo and Juliet. The first time we see him, during street fighting between the Montagues and Capulets at the very beginning of the play, he furiously resists Benvolio's attempts to stop the bloodletting, saying "What, drawn, and talk of peace! I hate the word/ As I hate hell, all Montagues, and thee./ Have at thee, coward!" (I, I, 77-9)

So . . . Shakespeare knows his astrology.

Of course, in employing astrological symbolism Shakespeare naturally focuses principally on the negative or shadow side of the archetypes, or where would the dramatic interest be? So though positive points could equally well be emphasized, the plays explore the challenges, difficulties, and moral imperatives associated with the symbols.

Usually astrologically-related keys are given in the first scene, which normally introduces the main characters, gives some necessary back-story, and reveals the thematic/archetypal basis of the play through its language.

Romeo and Juliet, oil on canvas, by Francesco Hayez

Romeo and Juliet, oil on canvas, by Francesco HayezRomeo and Juliet is no exception, although much of this information is given in a Prologue. In the form of a sonnet, a perfectly rhymed fourteen-line poem, the Prologue introduces

Two households, both alike in dignity,

In fair Verona, where we lay our scene,

From ancient grudge break to new mutiny,

Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean.

From forth the fatal loins of these two foes

A pair of star-cross'd lovers take their life;

Whose misadventur'd piteous overthrows

Doth with their death bury their parents' strife. . .

So we know that we are in Italy (Verona), where Mediterranean passions run high, and that the play will concern itself with TWO households, TWO lovers, and TWO foes, whose bitter hatred of each other has erupted anew. Since these households are "both alike in dignity", we might consider which zodiacal signs are "double-figured" and have two evenly balanced elements.

Only two signs have doubles in them: Pisces, with two interlinked fish swimming in opposite directions, and Gemini, represented by a glyph of two vertical lines connected by horizontal lines at the top and bottom. As we shall see, close examination of the play points to Gemini as providing its archetypal foundation. Gemini's planetary ruler is Mercury. How revealing that one of the principal characters, Romeo's friend, is even named Mercutio, obviously riffed from the planet itself!

The title of the play has two names in it. Sets of double individuals appear in myth, religious iconography, and legend: the twin brothers Castor and Pollox (one mortal and the other divine); siblings who are at the same time lovers (Isis and Osiris); and unrelated and fated male and female (Tristan and Iseult)—now including the literary characters Romeo and Juliet.

Twoness represents the esoteric principal of polarity, which can either resolve itself into unity or harmony (symbolized by the marriage of two human beings, or, on a grander scale, the marriage of heaven and earth), or remain polarized in tension and conflict. One of the unusual hallmarks of the language of Romeo and Juliet, something not characteristic of any other Shakespearean play, is the number of phrases using opposites, a poetic device known as oxymoron. When Romeo first hears about the opening fray in Verona's central square, he protests

Here's much to do with hate, but more with love.

Why, then O brawling love! O loving hate! . . .

O heavy lightness! Serious vanity! . . .

Feather of lead, bright smoke, cold fire, sick health!

Still-waking sleep, that is not what it is! . . . (I, i, 181-2, 186-7)

Juliet speaks similarly. After meeting Romeo and falling in love with him, despite not knowing his identity, she hears from her Nurse who he really is. Shocked, Juliet complains

My only love sprung from my only hate!

Too early seen unknown, and known too late!

Prodigious birth of love it is to me

That I must love a loathed enemy. (I, v, 140-4)

As planetary ruler of Gemini, Mercury gives us essential clues to the characters' actions as well as the moral messages of the play. Gemini is the first of the air signs in the zodiacal sequence, and correlates to the development of the mind and the subsequent ability to translate thoughts into words. The downside of Mercury's talents is being glib, talkative without saying anything of substance, superficial as well as changeable, mentally busy but endlessly distracted, and ingratiating but "phony"--in short, "mercurial".

Some of these negative talents well describe Mercutio, whom we first meet the evening that Romeo and his friends go to a masked ball at Capulet's home. (Mercury loves disguises.) Mercutio is a talker, someone who loves to hear himself speak, a true son of Mercury. He reveals his gift of gab in a very long speech triggered by Romeo's reference to a dream he has had that night. Beginning “O, then, I see Queen Mab hath been with you./ She is the fairies’ midwife, and she comes/ In shape no bigger than an agate-stone. . .” (I, iv, 53-55) and extending another 39 lines, the extended improvisation on fairy lore ends only when Romeo interrupts it with "Peace, peace, Mercutio, peace!/ Thou talk'st of nothing." (I, iv, 95-6)

The god Mercury is described in myth as a prankster. Shakespeare’s Mercutio can even joke as he is dying, stabbed by Tybalt's sword which passed under Romeo's arm. How many can make a pun as they bleed to death, "Ask for me tomorrow, and you shall find me a grave man"? (III, I, 100-2) Note that an ill-aspected Mercury has to do with mistimed or erratic action that misses its aims; hand-arm coordination that fails to synchronize; or efforts that stumble along the way.

The feminine counterpart to Mercutio is Juliet’s Nurse, whose first appearance on stage parallels Mercutio’s. Taking her cue from Lady Capulet’s reference to Juliet’s being of a “pretty age”, she proceeds to reminisce garrulously about Juliet’s weaning. In the 32 lines that follow, she even ends with the same sexual joke that Mercutio uses only one scene later. When the toddler Juliet had fallen upon her face, the Nurse’s husband had joked “Thou wilt fall backward when thou hast more wit”. (I, iii, 42) Mercutio’s wittier and more educated version speaks of the fairy queen Mab as one who “when maids lie on their backs,/. . . presses them and learns them first to bear,/ Making them women of good carriage.” (I, iv, 92-4) Like Romeo, Lady Capulet tries to stop the Nurse with “Enough of this; I pray thee, hold thy peace” (I, iii, 49), but she goes on for another 7 lines, repeating the same joke.

Like Mercury, the Nurse is capricious. When Juliet begs her advice after her father demands that she marry Paris, the Nurse ignores the fact that Juliet is already married to Romeo and reasons that “Romeo is banish’d; and all the world to nothing/. . . Then, since the case so stands as now it doth,/ I think it best you married with the County./ O, he’s a lovely gentleman! Romeo’s a dishclout to him.” (III, v, 215, 219-21) Juliet is outraged, for how can the nurse “dispraise my lord with that same tongue/ Which she hath prais’d him with above compare/ So many thousand times?” (III, v, 237-9) Clearly the opportunistic Nurse has changed sides.

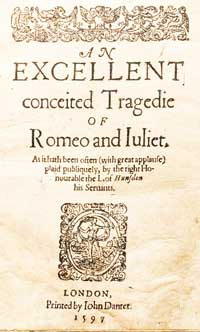

Romeo and Juliet, first edition title page

Romeo too seems fickle at the beginning of the play, going on and on about Rosaline whom he says he loves. But his elaborate articulations about love sound more intellectual than emotional (another downside of Mercury). At this point Romeo is clearly more fixated on the idea of being in love than he is actually feeling love. What a contrast to the genuinely passionate and intense emotion he has later for Juliet! No wonder, though, that Romeo’s friends, seeing such a sudden change, doubt his sincerity.

Despite their youth, the instant attraction between Romeo and Juliet is not an attraction between body and body, but soul and soul. Romeo intuits that Juliet is his soul-self when he declares "It is my soul that calls upon my name./ How silver-sweet sound lovers' tongues by night,/ Like softest music to attending ears!” (II, ii, 165-7)

How do we know that the instant mutual recognition of love between the two young lovers has a completely different quality than Romeo’s lovesickness for Rosaline? Because their interchanged lines to each other upon first meeting create a perfect sonnet, each line perfectly meshing with the other's. (See I, v, 95-109) Here we encounter the highest possible accomplishment of the Mercury-ruled mind: the ability to create exquisite and witty rhymed poetry. So the literal poetry of their first meeting reveals the compatibility of their intellects as well as their souls.

In Greek mythology Mercury was the gods' messenger, and with winged shoes and hat was capable of speedy transmissions between heaven and earth. Some of the tragedy in this play results from the lovers' impetuousness, rushing headlong into love and then into a secret marriage. Friar Laurence, religious advisor to both, (and chosen by Shakespeare to represent the opposite sign to Gemini, Sagittarius and its ruler Jupiter) admonishes them to "love moderately", to go "wisely and slow; they stumble that run fast." --good advice when trying to restrain Mercury's impulsiveness.

To be expected with a poorly-aspected Mercury, miscommunication abounds in the play, contributing to the lovers’ tragic fate. IF ONLY Capulet's servant hadn't happened to ask Romeo and Benvolio to read the party invitation because he was illiterate and couldn't; IF ONLY Benvolio hadn't urged Romeo to go; IF ONLY Juliet's parents hadn't decided just then to arrange a marriage for Juliet (who was already secretly married to Romeo); and most especially, IF ONLY Friar Laurence's letter had reached Romeo in Mantua so he would know that Juliet's appearance of death was false . . .

But all of this is dramatically necessary, for only with the ultimate sacrifice that both Romeo and Juliet make, to die for love, will the enmity between the two households die too—and polarity be resolved into harmony. The Prince of Verona chastises both the Montagues and Capulets when he says, "See, what a scourge is laid upon your hate,/ That Heaven finds means to kill your joys with love. . . All are punish'd". Old Capulet, Juliet's father, begs his former enemy "brother Montague, give me thy hand", and Old Montague, Romeo's father, offers to raise a statue of Juliet, significantly, in pure gold. (V, iii, 292-3, 296, 299) In sad recognition of the foolishness of their quarrel, all the characters make their exit as the onlookers contemplate the ultimate destiny of the two "star-cross'd lovers".

A short paper like this can only begin to show that viewing Shakespeare’s plays through an astrological lens can give great insights into the action, the characters’ qualities, and the deeper messages conveyed through the plays. It also reaffirms the idea that a great work of art, one that touches the hearts and minds of its viewers over a long time, is usually the particular expression of a numinous and abstract archetype, or it would not have universal appeal. I hope that this will inspire you to read and watch Shakespeare’s works with a new awareness of his masterful blending of artistic talent, esoteric thought, and the profound philosophical wisdom to be found in the astrological pantheon.

Other Notes

* See source notes about William Shakespeare's birth data.

Continue to Astrology and Shakespeare, Part 2

Priscilla Costello

Priscilla Costello, M.A., Dipl. CAAE, is a counseling astrologer, teacher and writer with a professional astrological practice spanning over 30 years. Teaching English also for over 30 years has given her a deep appreciation of Shakespeare, as well as the opportunity to synthesize the literary and the astrological. Founder and Director of The New Alexandria, a centre for religious, spiritual, and esoteric studies, she is the author of The Weiser Concise Guide to Practical Astrology (2008), a unique introduction to astrology linking it to psychology, religion, and esoteric wisdom. She is currently working on Shakespeare and the Stars, a book expanding her exploration of Shakespeare’s familiarity with esoteric wisdom.