Found in Translation : Ways and Means of Preserving a Classical Astrological Tradition

![]()

Dimitri Gutas asserts in Greek Thought, Arabic Culture, his study of the Graeco-Arabic translation movement in Baghdad and early Abbasid society, that Arabic becomes "the second classical language, even before Latin"[1]. According to Gutas, this ranking is due to the fact that "almost all non-literary and non-historical secular Greek books…available throughout the Eastern Byzantine Empire and the Near East were translated into Arabic"[2] from "about the middle of the eighth century to the end of the tenth"[3]. One of the happier and probably unforeseen consequences of this mammoth act of cultural transmission was the preservation (and eventual reintroduction to the West) of classical Hellenistic astrology.

Most historians concur that the chaotic societal upheavals, warfare, and pandemic illiteracy that besieged the Latin West during the early Middle Ages[4] had led to the virtual disappearance of scientific and philosophical learning throughout Europe (and in the classical world astrology could be classified as either) except for those subjects that somehow managed to endure in the quadrivium. Assuming that Greek is the first classical language to which Gutas makes indirect reference, there would seem to be little to question here about the pivotal importance of the Graeco-Arabic translation movement to the history of the Western astrological tradition - except, of course, what is meant by 'Greek', 'Arabic', and 'Hellenistic astrology'.

Scholar Robert Zoller in his book Fate, Free Will, and Astrology reminds the reader that "when we use the term 'Arabic' it is not necessarily to authors who were ethnic Arabs that we refer, but rather to writers who wrote in the Arabic language and their works in that language [t]hus …'Arabic' does not refer to the author's religion or ethnic origin"[5]. He proceeds to identify Masha'allah as a Jew, Abu Ma'shar as a Persian, and al-Kindi as an Arab, noting that all three wrote in Arabic. James H. Holden, meanwhile, writes that Greek, or Hellenistic, astrology was a system of "[h]oroscopic astrology [that] originated in Alexandria, Egypt in the second century B.C. as an amalgam of Babylonian, Greek, and Egyptian elements"[6] and notes that "it is called Greek astrology because the original treatises and most of those that survive from the classical period were written in that language"[7]- but not necessarily by Greeks.

Another classicist and translator, Robert Schmidt, clarifies that

[b]y Hellenistic astrology I mean the kind of astrology that was developed in Egypt and the Mediterranean area sometime after the Alexandrine conquest and continued to be practiced until the 5th or 6th century CE. This kind of astrology is the fountainhead of all late Western astrology, although over time it underwent numerous transformations, many of which were due to errors of translation, transmission and understanding.[8]

It is only now at the start of the twenty-first century that leading scholars in the field of astrological history have begun to seriously consider the impact and consequences that errors in 'transmission, translation and understanding' may have had upon the restoration and subsequent development of astrology in the West.

It is generally acknowledged that at least two, and possibly three[9], 'minor' translation movements in the Ancient Near East preceded the more renowned Graeco-Arabic translation movement of early Abbasid society. The first one took place almost 500 years earlier during the reigns of Ardashir I and Shapur I of the Persian-Sassanid empire (hereafter referred to as the Sassanian empire). Greek and Indian texts (including Ptolemy's Syntaxis) were translated into Pahlavi (a form of Middle Persian) during the 3rd and 4th centuries CE.

The Persian factor would prove to be a strong influence upon the Abbasid translation movement, and certain historians of science[10] have argued that in fact the Abbasid Graeco-Arabic translation movement was equally a Pahlavi-Arabic translation movement (particularly in regard to the legendary bayt al-hikma[11] ). The three Abbasid caliphs most strongly affiliated with the inception and execution of the translation movement, al-Mansur, al-Rashid and al-Mamum, were each profoundly impacted by key Persian advisors (or, in the case of al-Rashid, educators) with strong ties to Jundishapur, a city that served as a cultural juncture for the convergence of Persian-Sassanian, Syriac[12] and Hellenistic 'hermetic' influences[13].

A second translation and transmission movement was associated with the Nestorian Christians and the Nestorian schools in Edessa, Nisibis and Jundishapur where wisdom texts were gathered, preserved, and translated from Greek into Syriac. Therefore, one cannot discuss the role of Arabic culture in 'saving' the ancient Hellenistic astrological texts without also scrutinizing the role played by the Sassanian and Syriac cultures. Historian Scott Montgomery declares that

the true founding of the natural sciences within Muslim society came not from the uptake of Greek writings, but far more from materials long appropriated and nativized to Syriac, Pahlavi, and Sanskrit-speaking communities - materials…that is taken out of the hands and histories of these communities by being called Greek.[14]

Montgomery also notes that the term 'Greco-Arabic' "however useful as a retooled shorthand…still essentially erases centuries of history"[15]from the ανάγκη (anake) driven Eastward march of Hellenistic astrological, scientific, and philosophical texts.

Sassanian Astrology

It is necessary to discuss the role of India and the influence of its astrological and astronomical texts upon the Sassanians if one truly wishes to undo the erasure of these lost centuries. The direct trade route by sea that existed between Alexandrine Egypt and India in the late 1st century CE as well as the Roman Empire's establishment of Greek speaking colonies in India set the stage for direct transmission of classical Hellenistic astrological (and astronomical) techniques. Clear evidence of this transmission is to be found in the large number of Greek technical terms transliterated from Greek to Sanskrit. The following pairings of Greek and Sanskrit words are striking examples of this process of linguistic transmission: αναφορά/ anaphara, 'ώρα/ hora, μεσουράνημα/ mesurana, and κριός / kriya[16].

David Pingree, a noted translator and scholar of ancient Greek, Arabic, Persian, and Sanskrit texts, believes that prior to the 4th or 5th century BCE "much of the Mesopotamian omen literature, perhaps from Aramaic versions, was translated into an Indian language, and that these translations…form the basis of the rich Sanskrit and Pakrit literature on terrestrial and celestial omens"[17]. So, there was, in addition to direct transmission of Hellenistic astrology and astronomy to India, perhaps a shared Babylonian heritage common to the astral sciences of both India and Greece.

Pingree maintains "it is clear from the Indian texts of the 3rd to 6th century AD that many Greek texts in both sciences were rendered into Sanskrit."[18] One eventual impact of this long term transmission and assimilation process would prove to be the development of a system of Indian astronomical terminology which rivaled that of the Greeks in terms of specificity and sophistication. Indian terms such as 'sighrocca'[19]and 'mandaphala'[20] (from the Aryabhatiya[21]) would be in their turn transliterated into first Pahlavi then Arabic.

The Yavanajataka of Sphujidhvaja is one of the earliest known Indian astrological texts; it is based on a late 2nd century CE translation of an early 2nd century Greek[22] text thought to have been written in Egypt. The translation itself is credited to someone named 'Yavanesvara' which means "Lord of the Greeks' while the entire title translates as 'Greek Horoscopy'[23]. There can be little doubt, then, that some of the Indian astrological tradition was originally derived from Hellenistic astrology but adapted to the unique needs of their own cultural milieu. Historian Jim Holden stresses that

[t]he astrology (and astronomy) they obtained from the West was pre–Ptolemaic. Consequently, the classical Hindu astrology preserves features of older Greek Astrology, such as the use of the Sign House system of house division[24], the calculation of aspects by whole signs rather than by degree, and the use of a fixed zodiac[25].

Holden's statement that Indian astrology came from pre-Ptolemaic sources addresses a key issue that will be examined shortly. Indian astrology soon developed its own unique areas of expertise that distinguished it from the Hellenistic astrological tradition; these innovations and refinements included military applications of astrology (yatra) which mixed omen interpretation with καταρχαι[26] and also the astrology of interrogations[27] (prasnasastra).

The defining characteristics of Sassanian astrology were determined by circumstance - being in a position to receive dual transmissions from both Hellenistic and Indian sources and blend them with Zoroastrian doctrines (such as millenarianism). David Pingree who has written extensively on the subject on Sassanian astrology characterizes the Persian science as being too dependent upon "classical Greek astrology, of which only the material from Dorotheus, Valens, and Hermes has been as yet identified, [and] a smattering of Indian concepts and technical terms"[28]. The importance of the first degree of Aries[29] (i.e., zero degrees Aries) to Sassanian astrology leads one to wonder if the origins of the mundane 'world year transfer' charts[30] of Arabic astrology might eventually be attributed to the Sassanians as well.

The singular contribution of Sassanian astrology[31] that has no apparent ties with either Greece or India is a dynastic theory of astrological historicism founded upon "the influences of the periodically recurring Jupiter-Saturn cycles" [32]. This theory assumes that one can use the greater planetary conjunctions of astrology as a tool to chart the rise and fall of major political and religious empires, past and future. Such a preoccupation with the rise and fall of kingdoms was not unwarranted; the Sassanians were, after all, but one tribe in Ancient Iran. It was the desire to gain a political edge that motivated the early Sassanian kings to seek out astrological knowledge wherever they could find it[33]. The astral sciences were a means by which the political 'spinmeisters' of antiquity could grant any sovereign "divine imprint and sanction"[34]- a good thing to have as a ruler as it discourages immediate overthrow. Therefore, "the search for textual influence in astronomy was also, in large part, a search for political power…[and] an increased substance of terrestrial authority"[35]. Or, to quote the 9th century astrologer, al-Kindi, "whoever has acquired knowledge of the whole condition of the celestial harmony will know the past, present and future"[36].

The Sassanians received ερωτησεις, the aforementioned Indian branch of astrology known as the 'interrogations' (possibly based upon the καταρχαι outlined in Book V of Dorotheus' Pentateuch); they sought knowledge of the techniques of yatra as well and acquired translations of Sanskrit texts like the Brhadyatra of Varahamihira. This fusion of Hellenistic and Hindu influences happened over several centuries. Pingree cites " 'Umar's Dorotheus…the Bundahishn, and …Ibn Nawbakt's Kitab al-nahmatan"[37] as textual proof that many astronomical works were transmitted from Sanskrit into Pahlavi by the start of the 5th century. The Bundahishn contains the final element[38] of Sassanian astrology with no recognized precedent: a passage taken from a rare Pahlavi astrological manuscript that discusses the 'thema mundi', or horoscope of the world, here called 'zayc i gehan'[39]. However, the Pahlavi astrologer has placed the Moon's Nodes (Dragon's Head and Dragon's Tail) in the signs of Gemini and Sagittarius and added them to the lineup of dignified 'traditional' planets. David Pingree notes "these exaltations of the nodes do not occur either in Classical Greek or in Indian astrology, but represent a Sasanian innovation based on the Indians' inclusion of the two nodes among the planets"[40]. Pingree dates the passage to post 500 CE, probably during reign of King Anushirwan (531-78).

Syriac Translations

Although there was a strong Persian, or Sassanian, presence in the Muslim courts of the early Abbasid caliphates, the Syriac Christians were the true cultural ambassadors, or key intermediaries, for the transmission of astrological texts from Pahlavi to Arabic. They wore the mantle of biculturalism easily for the Syriac Christians, most notably the Nestorians and the Monophysites, had already enacted a similar role for the translation and transmission of Greek texts into Syriac. It is ironic that Christianity, in the extreme form of the Chalcedonian Orthodox Church, must be considered a prime agent of the distribution of Hellenistic 'pagan' texts (including astrological writings). After all, it was the Chalcedonian church's persecution of the Nestorians, in particular, that helped speed up "the nativizing of this work to different historical epochs and different cultural settings"[42]as the Nestorian Christians were forced east into cities and cultures that would ultimately become part of the Islamic Empire.

Nestorian communities took root and flourished within Persia and became widely known as centers of education and translation[43]. Such "enclaves of Hellenism…succeeded in imparting a taste for Greek culture and learning to influential Persians"[44]. Prior to their officially sanctioned persecution, some Nestorians had been moving east, anyway, in pursuit of fulfilling the missionary's dream of spreading the gospel to those who had yet to encounter logos [45].

In the late 5th century CE, Syriac translation became especially concerned with the transmission of the New Testament and other patristic texts. The Hellenization of the Syriac Church led to a heightened desire and perceived need for precision in translation of Greek texts into Syriac. In the early 6th century, Philoxenos of Mabbug, citing his dissatisfaction with earlier versions, initiated a new translation of the Bible. A shift of focus transpired in the nature of how Greek texts were translated into Syriac. Syriac translators of the 3rd and 4th centuries had been content, much like their Roman counterparts of an earlier era, to abandon "the stability and precision of Greek terminology…for more flexible, even vernacular, uses"[46] of their native tongue in textual transmission.

However, the desire to claim (or 'culturally appropriate') Greek texts by replacing them[47] once and for all with more literal, and therefore superior, Syriac translations called for a scholarly rejection of these earlier translations and the retrieval of the original Hellenistic source materials for a do-over. This quest for literalism carried over into translations of scientific and philosophical texts as well. The Syriac translators, therefore, faced the same problems that the Romans had: how does one translate a scientific text word for word when his language lacks any equivalent of the technical terminology in the text?

The Roman response had been to 'dumb down' the vocabulary or settle for inexact, or even willfully divergent, lexical reformulations of the technical terms in Latin. The Syriac translators chose a different path. Severus Sebokht, in his 7th century 'Treatise on the Constellations', could have been speaking on their behalf when he explains that

everything for which we intend to provide instruction- that is, make understandable to others- would not be teachable without the use of names and words ….[o]ne has neither the means or capability to teach or learn anything on the subject of what exists in nature without utilizing names and terminologies that are conventions and fictions"[48].

Syriac translators, attempting to stay faithful to the source texts, sought to recreate such Greek 'conventions and fictions' in their own tongue and, in the process, may have altered the basic nature of the Syriac language itself. Sebastian Brock, noting the increasing tendency of Syriac literature to adopt "not only large numbers of new Greek loan-words but also many features of Greek style"[49], suggests Syriac became a phihellenic language. Soon, particles and "complex lexical and syntactic calques"[50] became 'part and participle' of Syriac to allow translators room for their complex transliteral maneuvers. To sum up, Syriac became "a language that retained its Semitic qualities while adopting many Greek elements"[51].

The adaptation of Syriac to accommodate such Hellenizing influences of language and thought made Syriac, in its turn, an ideal 'intermediary' language between Greek and Arabic or even Pahlavi and Arabic. Just as Greek was a formative influence upon Syriac so Syriac was "a formative influence on Arabic during its transformation into a written, urbane, and sophisticated language"[52]. It is worthwhile to bear in mind when evaluating the transmission of Syriac texts of Hellenistic works into Arabic for translator error just how practiced the Syriac Christians were overall in their use and understanding of Hellenistic technical terms. The translations of Severus Sebokht (such as the one quoted above) demonstrate a thorough knowledge of Greek astronomical phenomenon, measurement and vocabulary. Historians Corbin[53] and Montgomery deem "the great period of Arabic translation…a more systematic continuation of the process begun long ago"[54] because "the fields initially chosen for particular attention by the Arabs were precisely those that had been selected by Syriac translators over the centuries"[55].

Hellenistic Translations

Some Arabic translators of 9th century Baghdad were well aware of their Syriac predecessors. For instance, Hunayn ibn Ishaq and his students considered Sergius Reshaina (a 5th century physician known for the excellence of his Galen translations) a veritable role model for translators[56]. It is not every translator who could claim, as Sergius did when referring to his rendering of Peri Kosmou by Pseudo-Aristotle "I have taken great care to remain entirely faithful to what I found in the manuscript , neither adding anything to what the philosopher wrote nor leaving anything out"[57]. Sergius was well aware that the two most common[58], and complementary, sins committed by translators of antiquity (for which there could be no textual absolution) were those of omission and conflation.

Both of these issues come to light when examining the writings of two Hellenistic astrologers, Dorotheus of Sidon and Vettius Valens, whose works have survived the centuries more or less intact. As copies of these coveted texts passed from one astrologer's hand to another, revisions were made, sections removed or accidentally omitted, and additional allusions, passages and charts interpolated into their chapters. The following itemization and reconstruction of such changes is drawn almost entirely from the historical detective work of David Pingree or James Holden. In the popular film adaptation of All the President's Men an investigative reporter is told by his 'deep' source to 'just..follow the money' in order to follow the flow of power (and its corresponding corruption) in circa 1970s Washington,DC. Similarly, the best advice for anybody wanting to understand the flow of information across geographic and linguistic boundaries in the Ancient Near East would be to "follow the texts".

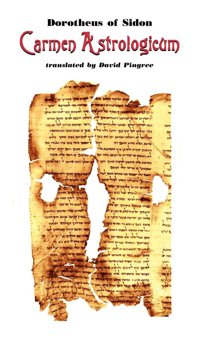

Dorotheus was a Hellenized Phoenician who lived and wrote in Sidon during the early 1st century CE. Dorotheus composed the Pentateuch (widely known as Carmen Astrologicum) in Greek sometime around the mid-to-late 1st century CE. There was an Arabic translation made in 800 CE by 'Umar ibn al-Farrukhan al-Tabari which seems to be drawn from an incomplete 3rd century Pahlavi translation. A passage in Kitab al-Nahmatan by Ibn Nawbakht quoted by ibn al-Nadim in al-Fihirst establishes that there was such a translation. Scholars have surmised that 'Umar's version is incomplete due to the existence of surviving fragments of an Arabic version of Dorotheus rendered by Masha'allah from a Pahlavi source as well. Portions of Masha'allah's version correspond to excerpts of Dorotheus that appear in Hephaistio of Thebes' Apotelesmatics but which are not present in the al-Tarabi translation of 800 CE[59].

Indeed, David Pingree believes that Masha'allah had access to "the Pahlavi original in longer, fuller form"[60] with additional commentary and cites as proof a long passage on lots attributed to Dorotheus that appears in the Hugo of Santalla translation of Masha'allah's Kitab al-mawalid al-kabir. Furthermore, 'Umar's text does not include Dorotheus' chapters on profession, on army service and on friendship. However, "some Indian theories were added - in particular that of navamas, or ninths of a sign"[61] to Book V, chapter V of the Pentateuch.

Pingree thinks that the Pentateuch was further tampered with by 3rd to 5th century Sassanian copyists and scholars. He points out that both 'Umar's and Masha'allah's versions feature Arabic transliterations of Pahlavi terms and two post second century charts[62] which were probably interpolated into the text by Sassanian astrologers since Dorotheus' own example horoscopes run the temporal gamut from only 7 BCE to 43 CE. There are, additionally, references to Vettius Valens[63], Allah[64], and Qitrinus al-Sadwali which do not fit into the accepted timeline for the life of Dorotheus and are therefore suspect and present only by the design of a latter era copyist, compiler, or translator[65].

Vettius Valens is referred to above as "Valens the Philosopher", an honorific which James Holden called "an obvious interpolation"[66]. Valens is thought to have lived during the 2nd century CE (although issues of textual interpolation in the works of Dorotheus have created minor confusion among historians about Valens' exact era[67]). The nine book Ανθολογιαι (Anthology) by Valens is ascribed a 2nd century date of authorship. According to Robert Schmidt, who has recently translated all nine books into English, "more than other any astrologer, Valens may represent the mainstream of the Hellenistic tradition [and] he quotes a large number of astrologers who would otherwise be unknown"[68].

Ανθολογιαι was translated into Pahlavi where it was known as Bizidaj[69], a title derived from the Pahlavi word 'Wizidag'. The Indian astrologers, on the other hand, knew this text as Befida. Ibn Hibinata, a mid-10th century Christian astrologer who lived in Baghdad, explains that the Pahlavi version was revised and commented upon by a 6th century CE figure named Buzurjimhr[70]. This Pahlavi version may have been "yet another compendium of astrological doctrines from the ancient classics"[71] which included portions of Valens' work. The Greek version of Ανθολογιαι ( which was not available in uncorrupted form in the West until such an edition was published in Germany in 1908[72]) veers markedly in the quality of its writing from chapter to chapter[73] which has led some scholars to theorize that only certain chapters are faithful 'translations' of Valens while others may be less skilled paraphrases of his work.

Nevertheless, one can assume at least four, and possibly five, versions of Valens survived in the Ancient Near East long enough to effect meaningful linguistic and geographic transmission. These well-traveled 'anthologies' would include the original Greek, the early Pahlavi translation[74], a Sanskrit version, the revised 'Buzurjimhr' 6th century Pahlavi version, and an Arabic translation. Interpolations in one surviving copy of Ανθολογιαι include an expansion of the lunar tables in Book 1, chapter 17 to circa 250 CE and the inclusion of the chart of Emperor Valerian. Sometimes (as is the case in a Latin translation[75] of Masha'allah's Kitab al-mawalid al-kabir) Ανθολογιαι is the interpolated text; chapters 21 and 22 from Book 1 are inserted into the middle of Masha'allah's 8th century work. In another short treatise on interrogations, "Masha'allah quotes from both Dorotheus and Valens"[76]. Pingree mentions "the Arabic translation of a Pahlavi work on catarchic astrology ascribed to Valens, the Kitab al-asrar"[77], as a possible source of Masha'allah's quotes since "the subjects of buying land and of government…are scarcely topics in our Greek Anthologies"[78]. These topics are certainly addressed by Dorotheus.

Interrogational Astrology

As mentioned earlier, Indian astrology refined the catarchic astrology of the Greeks into a more elaborate system of interrogational astrology known as prasnasastra. Thus, the transmission of astrological knowledge from Greece to India prior to the 3rd century is established. The earliest Greek texts which address καταρχαι (katarchai) or interrogational concerns are the Pentateuch and, later, the writings of Antiochus. However, in Book V, chapter V of Dorotheus, catarchic and horary streams of astrology are mixed together. Or, as Rob Hand phrases it, "the fifth book of Dorotheus is mostly about elections and only a little about questions"[79]. In fact, the 'horary questions' in Dorotheus are not phrased as questions per se but rather as subclauses of situations such as "[t]he courtship of a woman, and what occurs between a wife and her husband when she quarrels and scolds and departs from her house publicly"[80]. Further along in the text (could he be talking about the same couple?) one encounters the Dorothean admonition "if you want to know, if she returns to him, whether he will profit from her or will find joy and happiness or other than this in her, then look to the hour in which you are asked about this at the position of the Sun and Venus"[81].

These early examples of horary are interspersed with specific rules for electing times for all sorts of actions including when to buy an animal, depart on a journey or "teach a man a science or a writing"[82]. Pingree remarks how "chapters in Dorotheus on choosing the time to launch a ship or buy land become in Masha'allah chapters answering the questions of whether or not someone will do these things"[83]. Similarly, "a chapter on Dorotheus on the sick, of which we have a prose paraphrase by Hephaestios, is cartarchic, but appears interrogational in the Pahlavi Dorotheus"[84]. This Pahlavi, and later Arabic, tendency to recast elections as interrogations may be meaningful evidence that Sassanian astrologers received their major exposure to Dorotheus, and hence, interrogatory technique, from an Indian[85] transmission.

The presence of interrogations in The Pentateuch matters because it demonstrates that horary concerns were part of the Hellenistic astrological canon prior to their retransmission to the West through original Arabic works (which commenced when Stephanus the Philosopher traveled to Constantinople in the late 8th century). Some medieval astrologers of a later era in the West would misunderstand the situation since "they noticed that Ptolemy's Tetrabiblos was restricted to Natal (and Mundane) Astrology…another wrong idea arose: Natal Astrology was Ptolemaic but Horary Astrology must have been invented by the Arabs"[86]. This misapprehension ignited a 'witch hunt' of sorts as would-be 'neo-traditionalists' sought to purge any 'heathen' Arabic influences from their astrological repertory. Many basic and essential Hellenistic techniques, such as "house rulers and other features of Horary Astrology"[87], were summarily thrown out simply because they were not mentioned in the work of that last word in astrological authority, Ptolemy.

Ptolemy

If James Holden was to have the last word on Ptolemy, that word would probably be 'deviant'. Holden is intent on hammering home the point that the astrology Ptolemy wrote about "is a deviant version of the Greek Astrology at odds with the teaching and practice of 2nd century astrologers"[88]. In another passage, he reiterates "the fact that Ptolemaic natal astrology is a deviant offshoot of traditional Greek natal astrology"[89] . And, finally, for good measure, in A History of Horoscopic Astrology, Holden declares that "Ptolemy's astrological book, the Tetrabiblos, was really an abridged and deviant version of the standard Greek astrology of his day"[90].

Holden is just as insistent that the works of Dorotheus and Valens were largely representative of the mainstream of their art. He enumerates some of the many features of 'conventional' Hellenistic astrology that Ptolemy chose to leave out (whether by ignorance or by choice) and they include the use of lots, triplicity rulers, "houses as primary sources of signification"[91], the influences of planets in the signs and in the houses, "the influences of the mutual aspects of the planets"[92], as well as derived houses, dispositors, and "concurrent use of special parts for judgement on specific matters"[93]. To this list could be added monomoira, many 'divisions of time' chart progression techniques[94], the other major lots[95] of Hermes (besides Fortune) and how 'sect' alters planetary strengths in a radix figure. Also, Ptolemy fails to address important chart delineation methods such as the one in which "the originators of astrology were accustomed to count houses not just from the Asc[cendant] but also from the Sun, the Moon, the Part of Fortune, one of the other Parts, or a planet"[96] in order to arrive at a judgment.

An as epitomizer of the celestial art, however incomplete, Ptolemy sells short many of the subtle philosophical underpinnings of Hellenistic astrology as well. For example, the Hellenistic astrologers regarded time and space as separate concrete quanta; there was no conceptual counterpart to the modern abstract notion of a 'space-time continuum' whereby the pair are perceived to be as symbolically intertwined as the twin serpents on a caduceus. Demetra George explains that "Hellenistic astrologers employed a vast array of timing procedures, most of which are unknown to modern astrologers due to…ruptures in the transmission process"[97] in A Reader for Intermediate Hellenistic Astrology.

Rob Hand, in the same volume, discusses how any "method of converting allotments of space"[98], such as bounds, "to those of time"[99] must be understood within a philosophical context of the inherent integrity of periods of time. To the Greek astrologers, units of time and space ultimately reduce down to indivisible integers[100] which retain a specific 'existential' value that remains whole and, while symbolic, is never arbitrary. Just as smaller periods of time[101], intact, displaced larger periods of time[102] in the process of paralepsis, so did highly 'specific' moments of fate (unlocked by the archetypal presence of a sub-timelord in a particular 'bounds' degree) displace the course of a longer sequence of life for the individual.

The conversion of space into time, therefore, as an astrological technique, had its own unique piece to speak apropos to the dialogue of eidos-hule that was ongoing between the planetary sub-timelords and Timelords in ancient predictive methods such as Circumambulation through the Bounds[103]. If one discards the most effective and complex expressions of a discipline, as Ptolemy did, he is, in effect, eliminating the more sophisticated thought processes which they personify. Can a knowledge system, such as Greek astrology, be considered thoroughly 'transmitted' when the highest realization of its concepts, i.e. sophisticated components of predictive technique, get left behind? If the erudite Ptolemy, a Hellenized Egyptian of the Roman Empire, could "decline to present the ancient method of prediction…on account of the difficulty of using it and following it"[104] then how could Pahlavi, Syriac, or Arabic translators hope to succeed at the task of transmission?

Fortunately, some ancient shirtsleeves were rolled up and the attempt made. It is through Pahlavi, Arabic, and Latin translations, as well as the odd surviving Byzantine Greek manuscript, that modern astrologers have learnt of these 'non deviant' once standard Hellenistic methodologies. The works of Dorotheus, Valens, Yavanesvara, and Hermes arrived in Persia, Syria, and points east, several centuries in advance of Tetrabiblos. Therefore, the astrology of Ptolemy, instead of displacing these mainstream works (as it would in a later epoch) was blended with them by Muslim astrologers and the result was a hardy and dynamic hybrid.

Lost in Translation

One must not lose sight of the important fact that "those translators who brought the natural sciences into Arabic between the 7th and 10th centuries were people for whom Arabic itself was a second language"[105]. De Lacey O'Leary sensibly points out that "[i]n passing through the medium of a foreign language any form of intellectual culture is subject to modification"[106]. Since "[o]nce published, every text has a 'life' of its own, separate from that of its creator(s)"[107], should one accept as inevitable the slow accruement of interpolations, corrections (right or wrong) or commentary inserted into circulating copies of texts such as the Pentateuch or Ανθολογιαι?

Scott Montgomery maintains that "no classical author has come down to us in anything resembling an original form"[108] and postulates that 'authorship' in the Ancient world meant something different than it does in modern times[109]. For one thing, he believes that it was much more of a communal effort; one may think of it as a pyramid with the 'authority' on top, his students underneath him, followed by successive descending 'layers' of scribes, translators, archivists, and anthologists.

The 'Ptolemy' factor comes into play again running counter, in a Darwinian sense, to the best interests of Hellenistic astronomy and astrology. The latter was, of course, dependent upon the former for data, the zijs and 'Handy Tables', necessary for chart calculation. Since the reputation and popularity of Ptolemy's astronomical works eclipsed those of earlier Hellenistic astronomers, scribes, when faced with a choice of 'so many texts, so little time", might be excused for deciding to go with the Big Name in their copyist work. Ptolemy, and his immediate predecessors, wrote on "rolled, highly perishable material (probably papyrus)"[110] and for every text that got remade one can rest assured that there was another that rotted into obscurity.

The most careful archiving of papyrus texts could not prevent their eventual physical deterioration due to climatic factors such as heat, humidity, and seasonal surges in the insect population. In this sense, the ancient texts were truly 'Aristotelian' objects (even the non-Aristotelian texts) as they were subject to constant corruption and decay until more durable writing media such as codex, parchment, and paper became more widely available and affordable. The perishable quality of the written texts themselves necessitated the frequent copying over and remaking of any manuscripts one wished to preserve (whether for personal use or for the benefit of 'society'). Even the most meticulous scribe could be counted upon to make occasional mistakes and, in doing so, potentially transform the content of the text.

Does it even matter if minor alterations or omissions in the Hellenistic texts have occurred over the course of time so long as the most basic meaning has been successfully transmitted forward through the ages? After all, how do modern historians of astrological technique know for certain that integral parts of the Hellenistic system weren't purposefully left out and never written down in order to safeguard 'trade secrets' against those who would use the power of astrology for unscrupulous ends? Or, even, to ensure a steady client base! An anecdote is related about the 9th century Arabic astrologer, Abu Ma'shar; he is asked by a companion, Sadan

why he [Abu Ma'shar] did not mention this in his writings, 'when we were in Baldach'. The master replies that a sage who writes down all that he knows is like an empty vessel. No one needs him and his reputation declines. He should keep some secrets to himself and communicate them only to his closest friends.[111]

Apart from what has been lost to time, one may also wonder how much has been skillfully hidden? Any knowledge or technique which has been held back or cryptically encoded in the text is not, of course, available for translation. Robert Schmidt notes while discussing his translation of Introductory Matters by Paulus Alexandrinus (aka as Paul of Alexandria) that "Paulus' writing exhibits a strange sensitivity to the subtleties, overtones, and equivocations of Greek astrological terminology"[112] and wonders if "the reflective reader is supposed to be caught by certain words and phrases…[and] whether these are doorways to an esoteric level of the teaching, from which the unprepared, unworthy, or uninitiated are to be excluded"[113].

Even today practitioners of esoteric arts and sciences publish 'how to' guides that routinely omit essential steps and information preferring, perhaps wisely, to reserve such advanced knowledge for adepts a little further along 'the garden path'[114]. Perhaps one should not hope to resurrect or entirely comprehend Hellenistic astrology from writings divorced from their original Hellenized Near Eastern cultural context. The historian Lynn Thorndike believed that astrological treatises were, regardless of such speculations, invaluable cultural artifacts "that contribute to the context of history"[115] since "in trying to depict the future the astrologers really depict their own civilization"[116]. Thorndike, however, qualified his assumption by confronting

one difficulty. Does the author really picture his own society, or are his topics, which are supposed to represent the structure of contemporary civilization, really traditional categories long fixed by the rules of his art? And are the details of his subject matter his own intelligent adaptation of the general principles of his art to present conditions or are they slavishly copied from earlier manuals?[117]

This point seems a particularly valid one when applied to the many instances of interpolation of later era charts by translators and copyists in works such as the Pentateuch or Anthology. Rather than viewing these inserted charts as unwelcome and distracting instances of textual contamination, perhaps the historian of astrology better serves both his mistresses, Clio and Urania, when he approaches such tampering as a litmus test for the viability of the living tradition contained within the texts themselves? Do "the detailed and organized rules for establishing the outcome to almost any situation facing a citizen of the Greek World and the Roman Empire"[118] set forth in the Pentateuch apply equally well to an 8th century CE nativity tossed into the text by a 9th century Arabic astrologer? What 'intelligent adaptation' of astrological principles to 'present conditions', i.e. of 9th century Islam, has been made and what might the diligent astrologian therefore discern about the ostensibly evanescent nature of astrology itself?

Found in Translation

Astrology remains first and foremost an eidetic language of image. It is the language of day and night, up and down, one and two[119], and of heavenly bodies rising or setting on the horizon or staying, for a moment, suspended directly overhead; of planets melting into their proximity with the Sun; or coming together in dramatic alignments, conjunctions, and occultations. It is the language of number and dance and geometric relationships and of the stars which twinkle in a gentle but relentless morse code of neo-platonic pulsation.

There has never been a spoken or written language for which the message of astrology did not have to be supremely compromised in order to be expressed and understood. Before there was copyist error - indeed, before there was any writing at all- there was 'perceptual error': a misapprehension of what any given pair of human eyes was seeing when they looked up into the ink dark, star-studded heavens and experienced an inability to translate the perceptual overload of the moment into words.

Perhaps all that ever needed to be said was the Ancient Greek and dionysian equivalent of "wow". That would be an inclusive, if ambiguous, exclamation and as good a response as any to the astrologer's dilemma of how to prevent his most basic truth, that of man's connection to the kosmos of the Sky, from getting lost in the perpetual cycle of translation and transmission - whether from one arcane language to another, from night sky to human eye, or, even, from astrologer to client (a transmission, in this last instance, that spans the gulf of time from most ancient text to most post-modern practitioner of 'the round art'). If astrologers are successful in reclaiming and reassembling the unadorned loom of a 'mainstream' ancient Greek astrology (with all its attendant fine threads of pragmatic natal, mundane, and predictive techniques), they will most likely have to do so through the patient unraveling of Hellenistic thought from a tangle of texts, translations, and astrological traditions of manifold 'carrier' cultures.

And so one starts to pull at a thread, wondering how much of the 'essence' of the original semantics in surviving Hellenistic astrological texts has been lost in translation from Greek to Pahlavi to Syriac to Arabic to Latin or back into Greek since, as Robert Schmidt observed in his preface to Introductory Matters, "[t]he importance of Hellenistic astrology may not lie simply in what it said, but also in how it said it"[120] . During the subsequent decade, Schmidt has developed this train of thought further and now believes that "the restoration of Hellenistic astrology as a theoretical construct"[121], complete unto itself, is possible because "the technical Greek astrological terminology itself preserves this framework"[122].

If this theory is correct and "the founders of Hellenistic astrology …exploited the astonishing multivalence of the words of the Greek language"[123] themselves in order "to preserve and transmit the theoretical framework of this discipline…we can say that Hellenistic astrology was a symbolic language in the truest sense of the word". [124] In which case, one can only hope that the countless generations of Greek, Sanskrit, Pahlavi, Syriac, and Arabic translators[125], copyists, and compilers were men learned in nuance as well as language, and so, quite attuned to the philological possibilities of every syllable transmitted - true, indeed, to the fullest 'sense' of each word. The potency of astrology's message across the ages retains its full strength even while, like a homeopathic solution, it has been diluted time and again by the process of being first tapped then poured from one cultural container into another.

Scott Silverman

Scott Silverman is a consulting astrologer who currently resides in coastal Northeastern New England. He has been studying the symbolism and history of astrology since the mid-1980s and considers himself fortunate to have been one of the first students enrolled at Kepler College. His areas of extreme astrological interest include (but are not limited to) declination, Astrolocality, Uranian/Symmetrical, and Ancient Astrology. Scott is a long ago graduate of Vassar College and now wishes he had thought to major in Astronomy. He has edited a number of astrology books, as well as a series of special topic issues of NCGR Geocosmic Journal.

Endnotes

[1] Dimitri Gutas, Greek Thought, Arabic Culture (New York: Routledge, 1998), 2.

[2] Gutas, 2.

[3] Gutas, 1.

[4] Circa 500 to 900 CE.

[5] Robert Zoller, Fate, Free Will, and Astrology (Ixion Press, 1992), 53. Zoller states in a previous sentence on the same page 'When we in the west speak of medieval astrology it is to Arabic astrology that we inevitably refer'.

[6] James H. Holden, Ali'Abu Al-Khayat: The Judgement of Nativities (Tempe: American Federation of Astrologers, Inc.), 11.

[7] Ibid, 11.

[8] Robert Schmidt, Original Source Texts and Auxiliary Materials for the Study of Hellenistic Astrology (Cumberland: The Phaser Foundation, Inc.) Week 1, 3.

[9] The third is associated with early 11th century Byzantium and the translation (into Greek) of Arabic astrological texts by, among others, Masha'allah, Abu Ma'shar, Sahl ibn Bishr, al-Khayyat, and 'Ali ibn Ahmad al-'Imrani, none dating any later than the mid tenth century CE. See Pingree, From Astral Omens to Astrology: From Babylon to Bikaner (Rome: Institutio Italiano Per L'Africe E L'Oriente, 1997), 63-78. Dmitri Gutas, meanwhile, postulates a 9th century renaissance of secular translation in Byzantium whereby "the Greek manuscripts were copied in imitation of or as a response to the Arabic translations of these works…or they were copied because of specific Arab demand and under commission for these works". See Gutas, 185.

[10] Most notably, Dmitri Gutas.

[11] See Gutas, 53-60. According to Gutas 'hakim' originally meant 'wisdom' as in the wisdom of the sages (al-mutaquadimun) but eventually came to signify 'medical practitioner' as well due to the important role that the doctors of Jundishapur played in relation to bayt-al hikma.

[12] A 'local' dialect of Aramaic.

[13] The rebuilt city of Jundishapur was taken over by the Arabs in 738 CE. See O'Leary, 14-17, for an account of its re-establishment. The original city of Jundishapur (translation: near Shapur's camp) was founded by Shapur I in the third century as "a place to settle Greek prisoners taken in wars against the Roman emperor Valerian" and after the Sassanian capture of Antioch "many Greek speaking Syrians were given refuge in Jundishapur ..[t]hus, from the very beginning, the city acted as a nexus of Hellenism and cultural-linguistic mixing". Syriac, Pahlavi, Sanskrit, Armenian and early Arabic comprised the linguistic cultures mixing it up with Greek. See Scott L. Montgomery, Science In Translation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 79.

[14] Montgomery, 92.

[15] Ibid, 92.

[16] See Pingree, From Astral Omens to Astrology: From Babylon to Bikaner ( Rome: Institutio Italiano Per L'Africe E L'Oriente, 1997), 37.

[17] Ibid, 33.

[18] Ibid, 33.

[19] According to Scott Montgomery, sighrocca signifies "the apex of a planet's motion" and "mandaphala indicates a correction to a planet's apogee or aphelion". See Montgomery, 84.

[20] See preceding note.

[21] A 5th century Indian astronomical text.

[22] In his article "Astronomy and Astrology in India and Iran", Pingree asserts that the system and parameters of "the planetary theory given at the end of Sphujidhvaja's Yavanajataka …are precisely identical with those found on cuneiform tablets of the Seleucid period" and from this observation draws the conclusion "that at least some Greek astrologers ignored the epicyclic and eccentric theories developed by Apollonius, Hipparchus, and Ptolemy, and adhered to the Babylonian methods". He suggests that the originator of the Yavanajataka was "one such astrologer". See David Pingree, "Astronomy and Astrology in India and Iran", Isis, Vol. 54, No.2 (June, 1963), 229-246. He delineates the parallels in detail in his commentary on The Yavanajataka of Sphujidhvaja Volume II (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978), 407-413.

[23]' Jataka' on its own means 'horoscopy'.

[24] Now widely known as the Whole Sign House system.

[25] Holden, 14.

[26] Greek electional astrology.

[27] David Pingree clarifies that "[t]he difference between catarchic and interrogational astrology is that with the former the astrologer determines a propitious time for his client to begin doing something, while with the latter he answers a specific question from the horoscope of the moment at which the question was asked". See Pingree, From Astral Omens to Astrology, 36.

[28] Pingree, "Classical and Byzantine Astrology in Sassanian Persia" in Dumbarton Oaks Papers 43 (1989), 235.

[29] According to Indian tradition, it was at zero degrees Aries that the Grand Conjunction took place at the start of Kaliyuga - this same "Grand Conjunction …also was basic to the computation of the mean longitudes of the planets in the Indian astronomical systems that the Sassanians had based their own astronomy on" (Pingree, From Astral Omens to Astrology, 44).

[30] An annual chart cast for the moment the Sun enters the sign of Aries. Contemporary astrologers call it an Aries Ingress chart. James Holden considers it "a horary chart for which the question is 'what sort of year will it be for the people, animals, and crops in this particular location?". See A History of Horoscopic Astrology (Tempe: American Federation of Astrologers, Inc., 1996), 114, note 6.

[31] Buzurjmihr, the 6th century Sassanian minister, "was familiar with the method, and he cites from Jirash as an authority on the subject an astrologer with the obviously Iranian name of Hurmuzdafrid" (See Pingree, "Astronomy and Astrology in India and Iran", 245). See note 70.

[32]Ibid, 245.

[33] Tradition, in the guise of one passage from the fourth book of the Denkart and another from Kitab al-fihirst by Ibn al-Nadim which quotes Abu Sahl ibn Nawbakht, maintains that Ardashir I and Shapur I gathered astrological books from India and the Roman Empire and initiated "a massive program of translation into Pahlavi"(See Pingree, From Astral Omens to Astrology, 50).

[34] Montgomery, 86.

[35] Montgomery, 86.

[36] Peter Whitfield, Astrology. A History (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2001), 87.

[37] Pingree, "Classical and Byzantine Astrology in Sassanian Persia", 234.

[38] Apart from some specialized terms such as 'hilag' which had no Greek or Arabic equivalents and thus lived on through transliteration.

[39] Pingree suggests 'zayc i gehan' appears to be, as the nativity of Gayomat, the same Indian horoscope which first appeared in the Yavanajataka (270 CE).

[40] Pingree, From Astral Omens to Astrology, 40.

[41] He also speculates about a certain manuscript, "a Greek original that would have been translated into Pahlavi …in the later 3rd century" en route to becoming the Kitab al-mawalid of Zaradusht and was probably authored by "someone born at Harran on 9 April 232"- a someone who Pingree theorizes may have been Zaradusht's teacher, Aelius. The surfacing of lost texts may over time challenge scholarly consensus regarding which cultures are to be credited with which innovations in ancient astrology.

[42] Montgomery, 9.

[43] The bayt al-hikma was "primarily staffed by Nestorians". See David C. Lindberg, "The Transmission of Greek and Arabic Learning to the West" in Science in the Middle Ages (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978) 56.

[44] David Lindberg, 55.

[45] In A History of Medieval Islam, J.J. Saunders suggests that "Monophysite and Nestorian preachers helped to undermine Arab faith in the old gods and unwittingly contributed to the political upheaval" that would help to promote the agenda of the Islamic state. See Saunders, A History of Medieval Islam (London and New York: Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd., 1965) 12.

[46] Montgomery, 40.

[47] Montgomery writes that "an erasure of origins - the reader's forgetting that s/he is holding a foreign object rendered into the familiar- defines one of the primal aims of translation". See Montgomery, 13.

[48] Montogomery, 75.

[49] Sebastian Brock, "Greek and Syriac in Late Antique Syria". In Literacy and Power in the Ancient World, ed. A.K. Bowman and G.Woolf (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 149-160.

[50] Montgomery, 71.

[51] Ibid, 71.

[52] Ibid, 112.

[53] H. Corbin is cited by Scott Montgomery. See H. Corbin, History of Islamic Philosophy, trans. L. Sherrard. (London: Kegan Paul, 1993).

[54] Montgomery, 77.

[55] Ibid, 77.

[56] See Montgomery, 71-73. Treatises by Sergius include On the Causes of the Universe and On the Action and Influence of the Moon, the latter an adaptation of Book III of Galen's On the Natural Faculties

[57] Ibid, 73.

[58] In addition to copyist error, misunderstanding of the text and misappropriation of authorship.

[59] Pingree, From Astral Omens to Astrology, 46.

[60] Pingree, "Classical and Byzantine Astrology in Sassanian Persia", 229.

[61] Pingree, "Astronomy and Astrology in India and Iran", 241. See also Holden, A History of Horoscopic Astrology, note 93.

[62] One chart is for 20 Oct 281 and the other is dated 26 Feb 381(CE).

[63] Valens is thought to have lived a century later than Dorotheus.

[64] The references to Allah in particular indicate a post Islamic contamination of the text.

[65] Pingree believes this textual corruption can be traced back to the 6th century during the reign of Khusro Anushirwan (531-578 CE).

[66] Holden, A History of Horoscopic Astrology,

[67] See Nicholas Campion's introduction to the Ascella edition of Carmen Astrologicum , 12.

[68] Schmidt, Original Source Texts, Week 1, 11.

[69] 'Bizidaj' means 'Choice'. However, Pingree translates it as 'The Chosen'.

[70] Buzurjmihr was either the close associate of Khusro Anushirwan or "a contemporary 6th century Sassanian scholar named Burjmihr who…translated the Sanskrit Pancatantra into Pahlavi and introduced chess (caturanga) into Sassanian Iran". See Pingree, "Classical and Byzantine Astrology in Sassanian Persia", 231.

[71] Ibid, 231.

[72] At which point in time it may have had a great influence on the work of Alfred Witte.

[73] Were portions of it perhaps translated' back' into Greek from other languages to assemble a more complete version?

[74] Probably 3rd century CE.

[75] The example horoscopes in chapter 21 "can be dated from the original Greek though not at all from Hugo's weird Latin" which Pingree attributes to Hugo's ignorance of "Valens' astronomical and calendric data", noting that "his gibberish suddenly becomes intelligible when one imagines the Arabic and Pahlavi versions that lie between it and the original Greek". Hugo here refers to Hugo of Santalla. See Pingree, "Classical and Byzantine Astrology in Sassanian Persia", 231. David Lindberg, on the other hand, considers "Hugh of Santalla an exceptional stylist with a large vocabulary at his disposal" who "made no attempt to adhere strictly to the original". Lindberg, 78.

[76] Pingree, "Classical and Byzantine Astrology in Sassanian Persia", 231.

[77] Ibid, 231.

[78] Ibid, 231.

[79] Robert Hand, trans, Masha'allah. On Reception. (Arhat Publications, 1998), ii.

[80] Dorotheus of Sidon, Carmen Astrologicum, Translated by David Pingree (London: Ascella Publications, 1993) 134.

[81] Ibid, 138.

[82] Ibid, 134.

[83] Pingree, From Astral Omens to Astrology, 47.

[84] Chantal Allison, "The Ifriqiya Uprising Horoscope from 'On Reception' by Masha'allah, Court Astrologer in the Early Abbasid Caliphate", Culture and Cosmos, Vol.3, no.1, Spring/Summer 1999, 39.

[85] As opposed to a Greek transmission.

[86] Holden, Abu'Ali al-Khayyat: The Judgements of Nativities, 16.

[87] Ibid, 16.

[88] Ibid, 12.

[89] Ibid, 15.

[90] Holden, A History of Horoscopic Astrology, 44.

[91] Holden, Abu'Ali Khayyat: The Judgements of Nativities, 16.

[92] Ibid, 12.

[93] Ibid, 16.

[94] Such as 'circumambulations through the bounds' and the zodiacal releasing of the Part of Fortune and Spirit.

[95] These included the Lot of the Daemon, the Lot of Love, the Lot of Necessity, the Lot of Boldness, the Lot of Victory, and the Lot of Retribution.

[96] Holden, Abu'Ali al-Khayyat:The Judgements of Nativities, 17.

[97] Demetra George and Robert Schmidt, A Reader for Intermediate Hellenistic Astrology. Prepared for the Students of Kepler College (Phaser Foundation: 2003) Week 7, Lesson 1.

[98] Rob Hand, "The Relationship Between Periods and Directions" in A Reader for Intermediate Hellenistic Astrology, first page.

[99] Ibid.

[100] Such as a day, hour, or minute or an astrological zodia, bounds, or degree.

[101] One of the bounds of a sign.

[102] The sign itself.

[103] See George and Schmidt, "Introduction to Week One".

[104] Ptolemy, Tetrabiblos. Translated by F.E. Robbins (Cambridge: Loeb Classical Library) iii,1. Cited by Holden in A History of Horoscopic Astrology, note 105.

[105] Montgomery, 111-12.

[106] De Lacey O'Leary, How Greek Science Passed to the Arabs (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1951) 62.

[107] Montgomery, 14.

[108] Ibid, 19. Montgomery cites here the work of Reynolds and Wilson. See L.D. Reynolds and N.G. Wilson, Scribes and Scholars: A Guide to the Transmission of Greek and Latin Literature, 3rd edition (Oxford: Clarendon,1991).

[109] For a fascinating discussion on the nature of authorship in antiquity that uses Aristotle as an example, see Montgomery, 6-10. Montgomery makes a case that "Aristotle as an author probably never existed". He is following in the footsteps of Richard Shute who wrote way back in 1888 that "the Aristotle we have can in no case be freed from the suspicion (or rather almost certainty) of filtration through other minds, and expression through other voices". See Richard Shute, On the History of the Process by which the Aristotelian Writings Arrived at Their Present Form (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1888), 178.

[110] Montgomery, 20.

[111] Lynn Thorndike, "Abumasar in Sadan", Isis, Vol.45, No.1 (May, 1954), 30.

[112] See "Translator's Preface" in Paulus Alexandrinus. Introductory Matters. Translated by Robert Schmidt (Berkeley Springs: The Golden Hind Press, 1995), vi.

[113] Ibid, vii.

[114] The revised edition of a tantric text on my bookshelf provides the following random but excellent example. The author confesses that "the first edition presented many powerful techniques which traditionally had only been available…under the close supervision of a master. Realizing that those techniques, in their full power, could prove to be too intense for most people, as beginners, we didn't tell the whole truth. By leaving out a step, or doing something backwards, you lose the effect of the technique. This is how much of the work was presented". See Sunyata Saraswati and Bodhi Avinasha, The Jewel in the Lotus. The Tantric Path to Higher Consciousness (Sunstar Publishing, rev.ed., 1996),9.

[115] Lynn Thorndike, "A Roman Astrologer as Historical Source", Classical Philology, Vol.18, No 4 (Oct, 1913), 416.

[116] Ibid, 416.

[117] Ibid,417.

[118] See Nicholas Campion's Introduction to the Ascella edition of Carmen Astrologicum, 11.

[119] See the Platonic dialogue, Timaeus.

[120] Schmidt, Introductory Matters, vii.

[121] Robert Schmidt, Original Source Texts and Auxiliary Materials for the Study of Hellenistic Astrology (Cumberland: The Phaser Foundation, Inc.) Week 1, 4.

[122] Ibid, 4.

[123] Ibid, 4.

[124] Ibid, 4.

[125] Not to mention Pagan, Hindu, Zoroastrian, Christian, and Muslim.

References

Albumasar. Book of Flowers. Translated by James H. Holden. Revised second ed., (Phoenix: 1995) Privately published by the translator.

Allison, Chantel. "The Ifriqiya Uprising Horoscope from On Reception by Masha'allah"in Culture and Cosmos, Vol.3,No.1, Spring/Summer, 1999.

Ashmand, J.M., Ptolemy's Tetrabiblos. North Hollywood: Symbols and Signs, 1976.

Brock, Sebastian. "Greek and Syriac in Late Antique Syria". In Literacy and Power in the Ancient World, ed. A.K. Bowman and G.Woolf. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994, 149-160.

Dorotheus of Sidon. Carmen Astrologicum. Translated by David Pingree. London: Ascella, 1993.

Campion, Nicholas. "Dorotheus of Sidon: His Life and Significance" in Carmen Astrologicum by Dorotheus of Sidon, trans. By David Pingree. London: Ascella, 1993.

George, Demetra and Schmidt, Robert. A Reader for Intermediate Hellenistic Astrology. The Phaser Foundation, 2003.

Gutas, Dmitri. Greek Thought, Arabic Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early Abbasid Society. London and New York: Routledge, 1999.

Hand, Robert. "The Relationship Between Periods and Directions" in A Handbook of Intermediate Hellenistic Astrology by Demetra George and Robert Schmidt. Phaser Foundation, 1993.

Holden, James H. Abu'Ali Khayyat: The Judgements of Nativities. Tempe: American Federation of Astrologers, Inc., 1988.

Holden, James H. A History of Horoscopic Astrology. Tempe: American Federation of Astrologers, Inc., 1996.

Lindberg, David C., "The Transmission of Greek and Arabic Learning to the West" in Science in the Middle Ages. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978.

Masha'allah. On Reception. Edited and Translated by Robert Hand. Arhat, 1998.

Montgomery, Scott L. Science In Translation: Movements of Knowledge Through Cultures and Time. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000.

O'Leary, De Lacey. How Greek Science Passed to the Arabs. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1951.

Paulus Alexandrinus. Introductory Matters. Edited and Translated by Robert Schmidt. Berkeley Springs: The Golden Hind Press, 2nd edition, 1995.

Pingree, David. "Astronomy and Astrology in India and Iran", Isis, Vol.54, No.2 (June, 1963) pp.229-246.

Pingree, David. Classical and Byzantine Astrology in Sassanian Persia", in Dumbarton Oaks Papers 43 (1989), pp.227-239.

Pingree, David. From Astral Omens to Astrology:From Babylon to Bikaner. Rome: Institutio Italiano Per L'Africe E L'Oriente, 1997.

Pingree, David, trans. The Yavanajataka of Sphujidhvaja Volume II. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1978

Ptolemy. Tetrabiblos. Edited and translated by F.E. Robbins. Loeb Classical Library, 1940.

Saraswati, Sunyata and Avinasha, Bodhi. The Jewel in the Lotus. The Tantric Path to Higher Consciousness. Sunstar Publishing, Rev.ed., 1996.

Saunders, J.J., A History of Medieval Islam. London and New York: Routledge and Kegan, reprint, 1972.

Schmidt, Robert. "Translators Preface" in Introductory Matters by Paulus Alexandrinus. Berkeley Springs: The Golden Hind Press, 2nd edition, 1995.

Schmidt, Robert, Original Source Texts and Auxiliary Materials for the Study of Hellenistic Astrology. Phaser Foundation, 2002

Shute, Richard. On the History of the Process by which the Aristotelian Writings Arrived at Their Present Form. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1888.

Thorndike, Lynn. Lynn Thorndike, "A Roman Astrologer As Historical Source", Classical Philology, Vol.18, No 4 (Oct, 1913), 418.

Thorndike, Lynn. "Albumasar in Sadan", Isis, Vol. 45, No. 1 (May, 1954) pp.22-32.

Valens, Vettius. The Anthology Book 1. Translated by Robert Schmidt. Berkeley Springs: The Golden Hind Press, 1993.

Verbrugghe, Gerald P., and Wickersham, John M. Berossos and Manetho. Native Traditions in Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press,

Whitfield, Peter. Astrology. A History. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc, 2001.

Zoller, Robert. Fate, Free Will, and Astrology .Ixion Press, 1992,