ASTROLOGY IN EARLY MODERN ENGLAND

Foreword by H. Darrel Rutkin

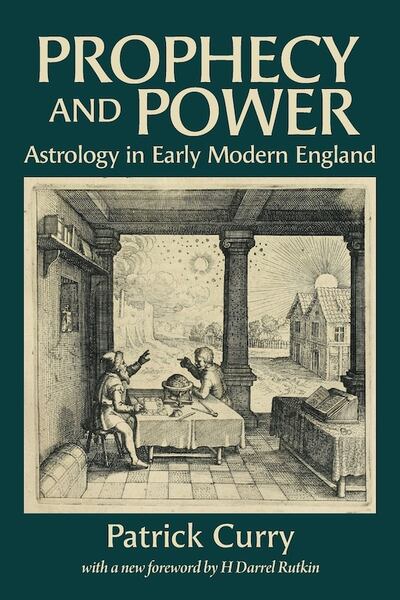

25 years after Frances Yates's epoch-making Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition (1964)[1] – and the same year that Kaske and Clark published their critical edition with English translation of Marsilio Ficino's De vita libri tres (which was itself published 500 years after the first edition in 1489)[2] – Patrick Curry published his Prophecy and Power: Astrology in Early Modern England, which would have a major impact on our understanding of the social, political and intellectual history of early modern astrology, especially in England.

Although our knowledge about the history of early modern astrology in Europe more broadly – including its medieval and Renaissance backgrounds – has advanced significantly in the last 30 years, Curry's seminal study has stood the test of time and has not yet been superseded. Hence, there is good sense in republishing it now in these literally millennial and apparently apocalyptic times, much as many of the 17th-century writers Curry describes understood their own times.

As my own scholarly interests started to move slowly but surely towards the history of astrology in the early 1990s, Prophecy and Power was one of the first books I read that took astrology seriously as a legitimate subject of historical research. One of the others I read at that time was Paola Zambelli's marvelous historiographical introduction to and study of the deliberately anonymous 13th-century Speculum astronomiae (often attributed to Albertus Magnus), along with a critical edition of the Latin text and an excellent English translation.[3] It seemed to me then – as it does even more so now – that the history of astrology, as an important and central but not well understood branch of the history of medieval, Renaissance and early modern European science, history and culture ca. 1250–1800, was finally starting to stand on its own two historiographical feet as a scholarly discipline, thereby joining the history of ancient Greco-Roman astrology, which had done so for significantly longer, despite the marvelous scholarship of Aby Warburg and his enviably erudite collaborators.[4]

I am delighted that Patrick has invited me to write the Foreword to his admirably readable, accessible and insightful study. The stories he tells about an extraoardinary cast of characters who all engaged significantly with astrology in early modern England made a strong and lasting impression on me, especially the politically engaged almanac writers on both sides of the conflict during the English Civil War and Interregnum, and his description of the Astrologers' Feasts with their regular meetings and astrologically informed sermons.[5]

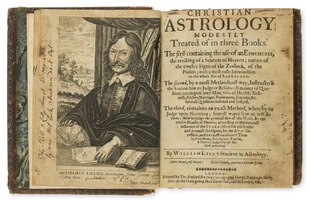

In addition to being encouraged at an early stage in my studies, I was also introduced to such lively, outsized and influential characters as William Lilly, George Wharton and John Booker as well as to John Gadbury and John Partridge in the next generation. I also learned that the serious astronomers, Edmund Halley and John Flamsteed, both provided the most accurate and up- to-date planetary data for George Parker's deeply astrological annual almanacs at the very end of the 17th century. Who knew? I certainly did not, but I was deeply inspired to learn more about the marvelous and lively characters I met on that first reading. The impression was indelible, as I am certain it will be to a new generation of readers – both scholarly and general – who will first encounter these colorful characters and their writings in Curry's lively and informed telling within their revolutionary cultural, political and religious contexts.

As he tells it (and properly following Keith Thomas's and Bernard Capp's still valuable studies from 1971 and 1979 respectively),[6] England was a relative latecomer on the early modern European astrological scene – not really coming into its own until the publication of William Lilly's vernacular textbook, Christian Astrology, in 1647 – despite significant medieval contributions as revealed in the scholarship of Charles S. F. Burnett on Adelard of Bath, Sir Richard Southern on Robert Grosseteste (especially the revised introduction to the 2nd paperback edition of 1992), Hilary M. Carey's Courting Disaster, and John D. North's Chaucer's Universe, among others.[7]

In fact, we now have a much fuller understanding of medieval European astrology's scientific and theological foundations – both conceptual and institutional – and their Renaissance and early modern continuities and developments. In relation to these, we may properly judge the continuities and transformations in Curry's story ca. 1640–1800 and their peculiarly English dimensions. This was precisely the time when astrology had reached its high-water mark there in learned culture and throughout society (ca. 1642–1710), and was then further popularized (and/or vulgarized) and largely delegitimized as knowledge and practice at the same time as its scientific and theological foundations were undermined and removed (ca. 1710–1800) in a process this is still not fully understood, and in which the English case is particularly significant.[8]

Although research on the history of medieval, Renaissance, and early modern astrology has made major strides since 1989 – in part inspired by Curry's pioneering efforts to take astrology seriously as a significant historical phenomenon,[9] and thus continue to correct for certain still current Enlightenment strategies of erasure and oblivion – there is still much work to be done. If we actually read what the range of astrologers wrote in depth and detail, and if we locate their writings solidly within their socio-political, cultural and confessional as well as their conceptual and institutional contexts – as Curry usefully does – a very different and much more interesting picture begins to emerge. This is all the more important and revealing as astrology seems to reside in a blind spot of the modern and postmodern Western psyche. In significant measure, Prophecy and Power gave more-recent scholars permission to take astrology seriously as a culture-historical and scientific phenomenon, much as historians of alchemy were also doing contemporaneously with their subject.[10]

The historiographical panorama of medieval, Renaissance and early modern European astrology has developed significantly since the appearance of Curry's study, especially for medieval astrology. I will be very brief in what follows in placing Curry's work in relation to the current range of scholarship, much of the highest quality. From my perspective, we cannot properly understand early modern developments in the history of astrology either in England or elsewhere in Europe within their various contexts without first understanding medieval astrology (ca. 1250–1500) within its proper conceptual and institutional contexts. Fortunately, there is now a much more solid historiographical foundation for doing so, primarily with the work of Jean-Patrice Boudet for astrology per se (and in relation to magic and divination) and Nicolas Weill- Parot for astrological magic or talismans – as well as David Juste's seminal researches into the manuscript remains of Latin astrology – and now Maria Sorokina's foundational study on the role of celestial influences and astrology in commentaries on the Sentences of Peter Lombard, ca. 1220–1340.[11]

Within this context, my work has attempted to reframe these and earlier studies and thereby provide an interpretive framework for more sharply articulating characteristic medieval structures, and then to use those foundational structures for analyzing Renaissance and early modern developments in greater depth and detail. I do this primarily by locating astrology within one of its most important institutional contexts: the curriculum of the finest medieval universities in the mathematics, natural philosophy and medical courses, by which it was passed down as "normal science" to further generations. Using this framework, we may more fully and accurately address the major questions of astrology's increasing popularization, and at the same time its delegitimation as knowledge and practice in learned culture during the 17th and especially the 18th century, one of the outstanding questions in the history of science and precisely the intent and timeframe of Curry's study.

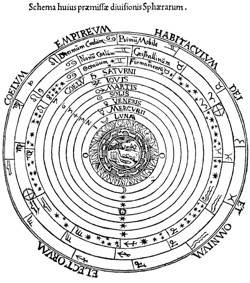

As discussed further below – and focusing primarily on both practical astrology and its scientific and theological foundations, as well as on its relationship to imagines astronomicae or talismans – I have attempted to trace both continuities and transformations within often radically transformed conceptual, institutional, socio-political and confessional contexts throughout Europe, ca. 1250–1800. These include a major set of profound transformations [1] from Aristotle to Plato and the Neoplatonists in philosophy from the 1480s onwards; [2] from Roman Catholicism to various forms of Protestantism (especially Lutheranism and Calvinism) in religion and theology from 1517 on, and [3] from Ptolemy to Copernicus and his followers in mathematical astronomy and cosmology from 1543 on. In my view, these epoch-making alternatives to Aristotle, Ptolemy and Roman Catholicism in their respective disciplinary domains collectively mark the beginnings of the Early Modern period in European science and culture.[12]

Within this much more solidly established historiographic framework, we can now more fully and accurately approach the context of astrology in early modern England and attempt to situate it within the rich and multifaceted situation throughout Europe.[13] There have been many marvelous book-length studies that more fully articulate our understanding of astrology's many roles in science, politics and culture throughout Europe.[14] In addition, I would like to highlight some recent collections of essays on various aspects of the history of astrology.[15] This is merely the tip of the historiographical iceberg. For a comprehensive and up-to-date bibliography on virtually every aspect of the history of astrology, see David Juste's regularly-updated bibliography on the Ptolemaeus Arabus et Latinus website.

As far as I can tell (and perhaps surprisingly, given the vast amount of primary sources that are now much more readily available on EEBO and elsewhere), there has not been much significant new research on astrology in early modern England since Curry's book appeared. Nevertheless, there have been some valuable studies published since then, including Ann Geneva's book on William Lilly; Anna Marie Roos on later expressions of astrological medicine, and Louise H. Curth's and Phebe Jensen's useful books on almanacs, including for the period just before that treated in Curry's book.[16] For astrology in the Elizabethan age, there has been important scholarship on John Dee, including works by John L. Heilbron and Wayne Shumaker, Nicholas Clulee, William H. Sherman, and Glyn Parry,[17] and perhaps most importantly, Lauren Kassel's groundbreaking researches on Simon Forman and his extensive manuscript Nachlaß in conjunction with her online Casebooks project.[18] For astrology in the English university context, Mordechai Feingold's Mathematicians' Apprenticeship (1984) is still fundamental. There is also a recent article by Martin Gansten (2013) on the uses of Placido Titi's astrological reforms in 19th- century England; Vittoria Feola on astrology and antiquarianism; Michelle Pfeffer on the astrologers' feasts (BJHS 2021), which I have already mentioned, and Mark Harrison's insightful essay on colonial medicine in the 19th century.[19] See now also Simon Dolet's recent and extensive MA thesis on the influence of English astrological reform from the time of Francis Bacon on Giuseppe Toaldo, Professor of Astronomy and Meteorology at the University of Padua from 1763–1797 and the founder of La Specola there.[20]

On this more solid and accurate historiographical foundation, I would now like to offer a brief review and critique – an updating and fine-tuning – of central framing structures that Curry used to approach his topic. Like Frances Yates before him, Curry's pioneering study inevitably did not get everything right – how could it? – although much of the prosopographical and factual material stands the test of time. Where I would primarily suggest fine-tuning and revision is in the broader framing structures that he employed, and especially how he described the basic patterns of practical astrology and their broader conceptual configurations.

[1] For better or worse, Curry's understanding of astrology is broadly framed and deeply conditioned by the now virtually ubiquitous overarching natural vs. judicial astrology distinction, which seems reasonable to us, but I increasingly believe is anachronistic and misleading, unless properly nuanced and historicized.[21] Thus, it is a good place to begin for revising the interpretive structure employed in his study. My discussion responds primarily to his introductory section, "Astrological Theory and Terminology" (8–15, esp. 8–12).

In fact, Curry divides up the four canonical types of practical astrology into two different groups, which he characterizes as two kinds of astrology, broadly speaking, natural and judicial. For Curry, "natural" astrology, which is close to natural philosophy, concerns astral influences on natural phenomena, such as weather and agriculture. It can make general and probable (i.e., not certain) predictions about large scale natural events and societal matters, including epidemics and plagues as well as political and religious transformations.

These correspond precisely to the traditional type of astrological practice called general astrology or revolutions – in particular, revolutions of the year (revolutio anni), as opposed to the revolutions of an individual's birth on any given birthday (revolutio nati). Revolutions of the year are concerned with the broader movements of the planets over time and their effects, and include historical astrology with its great, greater and greatest conjunctions of Jupiter and Saturn in their strikingly triangular patterns, which were treated (i.a.) in annual almanacs, where revolutions were the main type of astrological practice used.[22]

The other "kind" of astrology, then, a so-called "judicial" astrology concerned with predictions for specific individuals, is comprised of three specific types of astrological practice, namely nativities (birth horoscopes), elections (the choosing of astrologically propitious times to begin or do things, which Curry calls "inceptions"), and interrogations that purport to answer specific questions about any- and everything according to the time that the questions were asked or received by the astrologer, on the basis of which time a horoscope is cast. Curry calls these "horary" questions. As he correctly informs us, this latter practice was often controversial because it was usually unclear whether it fell afoul of legitimate astrological predictive practices that required a natural causal foundation. Otherwise, they would be considered a kind of divination, which relied on demons, at least according to Thomas Aquinas's influential analysis, to which Curry all-too-generally and briefly refers (p. 10), and about which we have learned a great deal more since 1989.[23]

Thus, if we remove this supposedly fundamental distinction between two purportedly different kinds of astrology – a so-called natural and judicial astrology – we are left precisely with the four traditional types of astrological practice, all of which require the use of horoscopes, and are thus all types of judicial astrology, with their knowledge-oriented type of interpretive practices, and they all require a natural causal basis to be considered legitimate.[24] In fact, the natural vs. judicial distinction was becoming normative during Curry's period, as we can see in Ephraim Chamber's influential article, "Astrology," in his Cyclopedia (1728), but this important issue requires further investigation and more precise historicization.[25]

[2] From my perspective, another set of problems for Curry's analysis arises when he then relates this purported distinction between natural and judicial astrology to "another important distinction: natural vs. supernatural," to which he also correlates a purported split between Aristotelian naturalism and Neoplatonic magic in relation to astrology, which he refers to as "a strain [= dividing] line among astrologers" (p. 9). In fact, during the period Curry is concerned with, Platonic and Neoplatonic metaphysical and sometimes magical views were increasingly prevalent, and at times – but not always – in some tension with Aristotelian views, which continued to be normative.[26] This also raises another problematic crux in the history of astrology, namely astrology's complex relationship to magic as well as to the other so-called occult sciences, a topic I will not further explore here.

Regarding natural vs. supernatural or magical, I believe that a more useful and accurate way to frame the distinction is between legitimate and illegitimate types of astrological (or better, predictive) practices, the lines for which were drawn differently at different times. For Thomas Aquinas, the distinction regarding the legitimacy of astrological predictions divided along the lines of predictions made on the basis of natural (= Aristotelian) causes vs. those made without a natural causal foundation that were thus derived from demonic interventions, which therefore were illegitimate and superstitious forms of divination.[27]

In the 16th century and beyond, there was also the further dimension of the increased accessability of Platonic and Neoplatonic philosophy after Marsilio Ficino had translated and/or paraphrased all of Plato's dialogues along with many of the Neoplatonists' writings in the 1480s and ‘90s. Ficino had also famously published his own astrologico-magical medical and ultimately theurgical text, the De vita libri tres in 1489, which had 30 further editions into the 17th century, but was not translated into English until the end of the 20th century.[28] The problem here with Curry's distinction between Aristotelian natural vs. [Neo]Platonic magical types of practices is that, once again, it seems like a reasonable bifurcation that could then be linked with the natural-judicial astrology distinction, but here even more so it is unclear what it actually refers to in practice.

In the end, if we are going to use a distinction such as natural vs. supernatural or magical, for an accurate analysis, we must define our terms more precisely, especially for "magic" or "magical." This is all the more important as that often in past historiography, "magic" was taken as the overarching category within which astrology itself was located, as we can see in Lynn Thorndike and Keith Thomas's famous and influential studies.

[3] Curry also presents a further problematic tripartite distinction of astrology's three different levels of sophistication (on pp. 11–12), with their respectively different modes of operating that he characterises as: [1] philosophical, [2] judicial, and [3] popular. This set of different approaches and practices at different social and educational levels also relates to his natural vs. judical distinction, but also in large part derives from his overly broad initial definition of astrology at p. 4:

have adopted a working definition of astrology to include any practice or belief that centred on interpreting the human or terrestrial meaning of the stars. […] Astrology does have a central feature, however, which such a definition brings out. That is the act of interpretation – in this case, of the stars: from [1] astral plant and weather lore of the simplest and most popular kind, or [2] the divinatory revelations of judicial astrologers,[29] to [3] the cosmic speculations of eminent natural philosophers.

Although he does not explicitly call them three different kinds of astrology (as he does with the natural vs. judicial distinction), but rather three different levels of sophistication and modes of operating, in fact they fall out as three different types of astrological (or astrology-adjacent) practices: on the bottom of the scale, the popular astrology found primarily in low-level almanacs; at the higher end, philosophical speculation based primarily on observation of the heavens and on cosmological reflections. In this view, both [1] and [3] relate primarily to society at large and the broader health and/or balance of the cosmos. These two astrological modes are then contrasted with judicial practices, which relate specifically to individuals and require the use of horoscopes, and are mainly practised by the middle classes and occur at a middle level of sophistication, whatever this means precisely.

To my lights, there are not and cannot be astrological practices properly so called without the use of horoscopes, even rudimentary ones. Thus, there is no philosophical astrology per se along the lines of Curry's formulation without the use of horoscopes, although it may well include the exploration and interpretation of celestial or cosmological phenomena, including comets. Without a horoscope, however, it is simply not a type of astrology, but rather some form of astrology-adjacent philosophico-cosmological speculation, and here we can see that Curry's overbroad initial definition has gotten him into some conceptual trouble, at least in my understanding.

These kinds of philosophical speculations can also sometimes include investigating how celestial influences work, and thus can relate to the articulation of astrology's natural philosophical foundations, which were normally taught in the natural philosophy course at earlier and contemporary universities. These researches certainly took place in the Italian, German, Spanish and Portuguese universities, for which we have clear evidence, in relation to core texts by Aristotle, especially the De caelo, De generatione et corruptione and Meteorologica.[30] Instead of this referring to astrological practices per se, for me this points, rather, to one of the most fundamental distinctions in understanding the history of astrology, namely, that between [1] the four canonical types of astrological practices and [2] the study of astrology's natural philosophical foundations in Aristotelian and later [Neo]Platonic, Cartesian and/or Newtonian natural philosophy, which seems to be in part what Curry is pointing towards here.

In my understanding, then, judicial astrology operates at all three educational and socio-political levels: popular-plebeian in almanacs (revolutions) for more general concerns, and for more personal-individual uses with nativities, elections and interrogations at both middling and elite levels, as we can see with Elias Ashmole and John Aubrey, among others. At the higher educational levels, there was also further exploration of celestial influences on both ontological and epistemological levels, i.e. what exists and what we can know about them, as in Robert Boyle's speculations, and especially regarding medicine in Richard Mead and others, as reflected in Ephraim Chamber's article "Astrology" in his Cyclopedia (1728), which was picked up whole and translated in Diderot and D'Alembert's Encyclopedie, as I discuss in my "Astrology." This was an important location where astrology's natural philosophical foundations were incorporated into and/or co-opted by natural philosophy and thereby separated from normal judicial astrological practices, which were often (but not always) disparaged from the 18th century on.

The best counterexample I know of to Curry's view on characterizing cosmological speculation as some sort of philosophical astrology is Isaac Newton and his providential understanding of how comets work within the economy of nature, many of whose speculations are certainly based on cosmological and religious conceptions.[31] There is, however, no evidence of anything explicitly astrological in any of Newton's many works both published and in manuscript, for which he seems to have had no positive interest whatsoever, for reasons I explore elsewhere.[32] This is probably also the case for William Whiston, whom Curry recounts in this context (pp. 146–47). These speculations are indeed cosmological and philosophico-providential, but not properly astrological, precisely because they do not have or use horosocopes, which thus becomes a very useful distinguishing criterion. This stands in contrast to most cometary speculations, which most certainly were astrological, and often employed horoscopes of the phenomena that located them in relation to the zodiac in order to interpret them.[33]

[4] The next and final step in Curry's broader interpretation as I understand it – and perhaps his most important contribution – is to try to correlate the types of astrology thus articulated along the socio-economic, political and religious spectrum. Here he relates [1] a so-called popular plebeian and magical astrology with the lower classes (Chap. 4); [2] judicial astrology requiring horoscopes with the middling and professional classes (Chap. 5), and [3] his so-called philosophical astrology with the educated and elite classes (Chap. 6).[34] The general desire to associate the broad range of astrological practices with various parts of the socio-economic and educational spectrum is certainly a question worth asking and building up an interpretation about, as he has usefully done, although it too could be fine tuned along the lines indicated above.

My criticisms and suggestions here should all be taken within the context of the broader realization that it is not at all an easy or simple matter to devise a good overall structure of interpretation. This should be done for the extensive transformative period from 1640 to 1800 within its complex sociopolitical, religious and scientifico-philosophical contexts together with the existence and ever increasing importance of the printing press – with almanacs being without a doubt the major site of astrology's public expression in society at all levels. This lasted intensively through 1700 or so, and then became less politically provocative and more popular,[35] but was especially vibrant (as one would expect) during periods of political instability and uncertainty, as was the case from 1642 to 1660 during the Civil War and Interregnum and at different points between then and 1690 or so, as the almanacs tried passionately to inform and shape public opinion with partisan intentions at various levels of society, as Curry rightly emphasises.

The attempt to locate specific practices and expressions at different social levels is well worth attempting despite the difficulties of doing so. Although it is somewhat schematic, I think that Curry was most successful here, especially in trying to describe the relations of class to various astrological practices. These configurations can be tricky to articulate individually, and this is even more so the case when they are joined together. Nevertheless, Prophecy and Power still provides a good and useful first approximation to these and many other individuals and issues, but 30 years on, we are in a better position to refine and sharpen his approach.

Finally, instead of closely associating Curry's three modes of astrology with the three schematically articulated socio-economic classes, I think that we are better and more accurately served by discussing three (or more) different levels or registers of how astrology was expressed, used or communicated by, to and within the different strata of society in relation to their different educational capacities, values and concerns, both public and private. Here is precisely where Curry's insistence in the concluding Chapter 7 on mentalities, ideologies and hegemonies in relation to the three socio-economic classes he articulates within shifting politico-religious dynamics can most usefully be employed, and should be more fully developed in subsequent research. This also includes the attempts at controlling and shaping public opinion by means of the ideological dimensions of almanacs, especially in the 18th century, as Curry rightly argues.[36]

Conclusion

In my view, Patrick Curry's Prophecy and Power very usefully maps out the complex terrain of astrology in early modern English society and culture ca. 1640–1800, thereby providing a valuable introduction and orientation to an important and increasingly better understood subject. This can then provide foundational material for many detailed microhistories within their complex socio-political, intellectual and confessional contexts, from the English Civil War to the Popish Plot and beyond, which has yet to be done. Now we need to fine-tune our understanding and sharpen the questions we are asking about what astrology is and how it was used in society on many levels within this broader framework. Some of Curry's more overly simple dichotomies were helpful for a first approximation, but should now be fine-tuned and refined based on our now more accurate understanding. I have offered some suggestions here based on the 30 years of intervening scholarship, but it will be up to the next generation of scholars to bring this pivotal portrait into sharper focus, in part by more fully comparing it to contemporary developments in other European countries – including its teaching in the universities there and its subsequent removal – as we move closer to a comprehensive account.

Finally, I would like to briefly reflect on the extraordinary timing of the reprint of Curry's book in relation to the new-style Great Conjunctions of Saturn and Pluto in Capricorn in January 2020 and of Jupiter and Pluto in April 2020 as well as the old-style Greater Conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn in Aquarius in December 2020. Among other things, these seem to have functioned as portents and/or harbingers of two of the most difficult and undoubtedly transformative years in contemporary history with numerous millenial and apocalyptic overtones. These famously included outsized fires and floods all over the world, not to mention an international pandemic (= plague) – and all within a context of intensifying socio-economic and political tensions on local, national and global scales – in a world undoubtedly undergoing extremely profound transformations, which are fully comparable with the related revolutionary developments in the premodern world as described in Curry's book.

Like them, we too can only use the conceptual tools and associated resources at our disposal to try to understand what on earth is happening. Perhaps we can learn something valuable about these and other related transformational matters from astrologers in history, who were themselves grappling with and reflecting upon similar transformative processes, but with a different set of interpretive tools within a vastly different conceptual framework than what we use now, but within the very same world of life here on earth within a cosmic context, however differently conceived. Perhaps we have something important to learn from them. Only time will tell, as ever. Regardless, this timely reprinting of Patrick Curry's very useful and insightful book can help orient us towards some very interesting thinkers and powerful writers in their richly dramatic culture within their own intellectual and socio-political contexts during an intensely transformative and (r)evolutionary period, which may not, in the end, be so very different from our own!

H Darrel Rutkin

Università Ca' Foscari Venezia[37]

H Darrel Rutkin

H Darrel Rutkin is a historian of science and philosophy with a Ph.D from Indiana University. He specializes in the history of medieval, Renaissance and early modern astrology, ca. 1250-1800, and is also keenly interested in the current state of astrological practice(s) in the West and around the world. His historical work focuses on astrology’s numerous relationships to science, theology and magic within their relevant conceptual, institutional, confessional, socio-political and cultural contexts over the longue durée. Some of his most recent work has addressed astrology’s centrality to the premodern Aristotelian-Ptolemaic understanding of nature, both conceptually and institutionally. He then uses these structures to reveal the complex patterns of how astrology was marginalized and ultimately removed from the map of legitimate knowledge and practice during the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment, thereby becoming an esoteric discipline. He is the author of Sapientia Astrologica: Astrology, Magic and Natural Knowledge, ca. 1250-1800 and co-editor of Horoscopes and Public Spheres.

Endnotes

[1] Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[2] Marsilio Ficino, Three Books on Life, Carol V. Kaske and John R. Clark (ed and trans), (Binghamton, NY: Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, 1989).

[3] Paola Zambelli, The Speculum astronomiae and its Enigma: Astrology, Theology and Science in Albertus Magnus and his Contemporaries (Dordrecht: Kluwer, 1992).

[4] Aby Warburg, The Renewal of Pagan Antiquity, David Britt (tr.), (Los Angeles: Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities, 1999), including his foundational studies on Renaissance astrology, "Pagan Antique Prophecy in Words and Images in the Age of Luther" (1920) and "Italian Art and International Astrology in the Palazzo Schifanoia, Ferrara" (1912).

[5] For a fuller picture of the astrologers's feasts, see now Michelle Pfeffer's valuable recent study, "The Society of Astrologers (c. 1647–84): Sermons, Feasts and the Resuscitation of Astrology in Seventeenth-Century London," British Journal for the History of Science 54 (2021): 133–53.

[6] I will not make full citations to studies that are in Curry's original bibliography, as these two were, along with Mary Ellen Bowden's still useful Yale PhD thesis from 1974.

[7] Adelard of Bath: An English Scientist and Arabist in the Early Twelfth Century, Burnett (ed), (London: Warburg Institute, 1987); Southern, Robert Grosseteste: The Growth of an English Mind in Medieval Europe, 2nd ed, (Oxford: Clarendon, 1992); Carey, Courting Disaster: Astrology at the English Court and University in the Later Middle Ages (London: Macmillan, 1992), and North, Chaucer's Universe (Oxford: Clarendon, 1988). One should now add to these Seb Falk, The Light Ages: The Surprising Story of Medieval Science (UK: Allen Lane, 2020).

[8] I have attempted a preliminary sketch of these European developments in my "Astrology," in The Cambridge History of Science, Vol. 3: Early Modern Science, Lorraine Daston and Katharine Park (eds), (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006, 541–61), and more recently in my "How to Accurately Account for Astrology's Marginalization in the History of Science and Culture: The Essential Importance of an Interpretive Framework," in a special issue of Early Science and Medicine edited by Hiro Hirai and Rienk Vermij, 23 (2018): 217–43. Most of this story still remains to be told in the rich detail that it deserves. I hope to fill in more of the picture in my volume III (reference just below). The English story should now be told in relation to Dmitri Levitin's extraordinary revisionist study, Ancient Wisdom in the Age of the New Science: Histories of Philosophy in England, ca. 1640–1700 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015). I wonder what he would have discovered had he also asked the questions about celestial influences in addition to those he asked about matter theory.

[9] These include his editing of a valuable collection of essays in 1987: Astrology, Science and Society: Historical Essays.

[10] See the fuller historiographic review in the overall introduction to volume I of my monograph, Sapientia Astrologica: Astrology, Magic and Natural Knowledge, ca. 1250–1800, Cham, SW: Springer, 3 vols. Volume I, "Medieval Structures (1250–1500): Conceptual, Institutional, Socio-Political, Theologico-Religious and Cultural," 2019, xlix–lvii. On alchemy in England, see now Jennifer M. Rampling, The Experimental Fire: Inventing English Alchemy, 1300–1700 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020), with relevant comparanda, and some overlap, including famously Elias Ashmole. Astrology and alchemy are often configured today as members of the so-called occult or esoteric sciences, but of course they have very different conceptual content, practices and overall histories, as articulated pointedly and persuasively in the editors introduction to Secrets of Nature: Astrology and Alchemy in Early Modern Europe, William R. Newman and Anthony Grafton (eds), (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001), and in other studies by Newman and Lawrence M. Principe, both individually and collectively.

[11] Boudet, Entre science et nigromance: Astrologie, divination et magie dans l'Occident médiéval, XIIe-XVe siècle (Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne, 2006); WeillParot, Les "images astrologiques" au Moyen Âge et à la Renaissance: Spéculations intellectuelles et pratiques magiques (XIIe-XVe siècle) (Paris: Champion, 2002); Catalogus Codicum Astrologorum Latinorum I: Les manuscrits astrologiques latins conservés à la Bayerische Staatsbibliothek de Munich, David Juste (ed), (Paris: CNRS Éditions, 2011); vol. II (2015) is for the Bibliothèque nationale de France à Paris; Sorokina, Les sphères, les astres et les théologiens: L'influence céleste entre science et foi dans les commentaires des Sentences (v. 1220–v.1340), 2 vols., (Turnhout: Brepols, 2021).

[12] I offer an analytic periodization in my vol. I (xxi–xxv) that develops and sharpens the ideas adumbrated here.

[13] And increasingly so around the world, including the New World (both North and South America) and the Far East, including Japan and China with the Jesuit missions there, but I will not explore this here.

[14] Fine examples are: for Italy, Anthony Grafton, Cardano's Cosmos: The Worlds and Works of a Renaissance Astrologer (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), and Monica Azzolini, The Duke and the Stars: Astrology and Politics in Renaissance Milan (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013); for Germany, Gerd Mentgen, Astrologie und Öffentlichkeit im Mittelalter (Stuttgart: Hiersmann, 2005), and Robin Barnes's Astrology and Reformation (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016); for Spain, Tayra Lanuza Navarro, "Astrologia, Ciencia y Sociedad en la España de los Austrias" (PhD thesis, Universitat de Valencia, 2005); for France, Jean-Patrice Boudet, Astrologie et politique entre Moyen Age et Renaissance (Florence: SISMEL, 2020), and Hervé Drévillon, Lire et ecrire l'avenir: l'astrologie dans la France du Grand Siecle, 1610–1715 (Seyssel: Champ Vallon, 1996); for the University of Edinburgh, see Jane RidderPatrick, "Astrology in Early Modern Scotland, ca. 1560–1726" (PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh, 2021); for Portugal, Luis Miguel Carolino, Ciência, Astrologia e Sociedade: A Teoria da Influência Celeste em Portugal, (1593–1755), (Lisbon: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 2003), and Luis Ribeiro, "Transgressing Boundaries?: Jesuits, Astrology and Culture in Portugal (1590–1759)," (PhD thesis, University of Lisbon, 2021). Regarding Copernicus and astrology, see Robert S. Westman, Copernican Question: Prognostication, Skepticism, and Celestial Order (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), and Pietro Daniel Omodeo, Copernicus in the Cultural Debates of the Renaissance (Leiden: Brill, 2014). For the significant Arabic influences on Renaissance and early modern astrology, see Dag Nikolaus Hasse, Success and Suppression: Arabic Sciences and Philosophy in the Renaissance (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016). More works could be added to this list.

[15] Secrets of Nature; Horoscopes and Public Spheres: Essays on the History of Astrology (Günther Oestmann, H. Darrel Rutkin and Kocku von Stuckrad [eds], Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2005); Nello specchio del cielo: Giovanni Pico della Mirandola e le Disputationes contro l'astrologia divinatoria (Marco Bertozzi [ed.], Florence: Olschki, 2008); Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 41 (2010), Special Issue, Stars, Spirits, Signs: Towards a History of Astrology 1100–1800 (Robert Ralley and Lauren Kassell [eds]); Il linguaggio dei cieli: Astri e simboli nel Rinascimento (Germana Ernst and Guido Giglioni [eds], Rome: Carocci Editore, 2012); A Companion to Astrology in the Renaissance (Brendan Dooley [ed], Leiden: Brill, 2014), several of the essays in which must be treated with caution; Philosophical Readings 7 (2015), a special issue on astrology edited by Donato Verardi; Astrologers and their Clients in Medieval and Early Modern Europe (Wiebke Deimann and David Juste [eds], Cologne: Böhlau Verlag, 2015); From Masha'allah to Kepler: Theory and Practice in Medieval and Renaissance Astrology (Charles Burnett and Dorian Gieseler Greenbaum [eds], Ceredigion, Wales: Sophia Centre Press, 2015); De Frédéric II à Rodolphe II: Astrologie, divination et magie dans les cours (XIIIe-XVIIe siècle), (Jean-Patrice Boudet, Martine Ostorero and Agostino Paravicini Bagliani [eds], Florence: SISMEL – Galluzzo, 2017); and a special issue on the marginalization of astrology edited by Hiro Hirai and Rienk Vermij in Early Science and Medicine 22 (2017), 405–516.

[16] Ann Geneva, Astrology and the Seventeenth Century Mind: William Lilly and Ann Geneva, Astrology and the Seventeenth Century Mind: William Lilly and the Language of the Stars (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995); Roos, "Luminaries in Medicine: Richard Mead, James Gibbs and Solar and Lunar Effects on the Human Body in Early Modern England," Bulletin of the History of Medicine 74 (2000): 433–57, and Luminaries in the Natural World: The Sun and Moon in England, 1400–1720 (New York: Peter Lang, 2001); Curth, English Almanacs, Astrology and Popular Medicine: 1550–1700 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007), and Jensen, Astrology, Almanacs, and the Early Modern English Calendar (London: Routledge, 2021).

[17] John Dee on Astronomy: Propaedeumata aphoristica (1558 and 1568), ed. and trans. Shumaker; introductory essay by Heilbron, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978); Clulee, John Dee's Natural Philosophy: Between Science and Religion (London: Routledge, 1988); Sherman, John Dee: The Politics of Reading and Writing in the English Renaissance (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1995); Parry, The Arch-Conjurer of England: John Dee (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), and Jennifer Rampling's edited collection with further bibliography; "John Dee and the Sciences: Early Modern Networks of Knowledge," Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 43 (2012).

[18] Medicine and Magic in Elizabethan London: Simon Forman, Astrologer, Alchemist, and Physician (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005). The URL for the Casebooks Project is: https://casebooks.lib.cam.ac.uk/.

[19] Gansten, "Placidean Teachings in Early Nineteenth-Century Britain: John Worsdale and Thomas Oxley," in Astrologies: Plurality and Diversity, Nicholas Campion (ed.), (Lampeter, UK: Sophia Centre Press, 2011), 109–24; Feola, "Antiquarianism, Astrology and the Press in William Lilly's Network (?)," in Antiquarianism and Science in Early Modern Urban Networks, Paris: Blanchard, 2014, 185–203, and Harrison, "From Medical Astrology to Medical Astronomy: Sol-lunar and Planetary Theories of Disease in British Medicine, c. 170–1850," British Journal for the History of Science 33 (2000): 25–48.

[20] He is currently working on his PhD thesis on Toaldo and his astrometeorological reforms at the University of Nice. I should also mention Fabrizio Bonolì and Daniela Piliarvu's valuable study of the teaching and practice of astrology at the University of Bologna from the 13th century to the present (I Lettori di astronomia presso lo studio di Bologna dal XII al XX secolo, Bologna: CLUEB, 2001); and the little known study of Andrea Argoli, Professor of Mathematics at the University of Rome and at Padua (Guiseppe Monaco, Andrea Argoli: Astronomo e medico del Seicento, Tagliacozzo: Scacco Matto Edizioni, 2007). Finally, I should mention Richard Mead's medical student and protégé, Samuel Jebb, who produced the Editio princeps of Roger Bacon's Opus maius in London in 1733, whom John Dee had also praised in his Propaedeumata aphoristica of 1558.

[21] For fuller methodological reflections on these and other topics in the history of astrology, see my "Understanding the History of Astrology Accurately: Methodological Reflections on Terminology and Anachronism," Philosophical Readings 7 (2015): 42–54 (a special issue on astrology edited by Donato Verardi), and xxv–xxxiii of the overall introduction to my vol. I.

[22] See Alexandre Tur's foundational PhD thesis for the fullest study of such matters; "Hora introitus in Arietem: Les prédictions astrologiques annueles latines dans l'Europe du XVe siècle (1405–1484)," Université d'Orléans, 2018. These revolutions of the year and their great conjunctions also relate directly to the astrological means by which God providentially governs all life on earth, but that is another story that I cannot go into here now. In the meantime, see Chap. 5 of my vol. I for influential medieval views on these matters by Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas. The "natural" in natural astrology rhetorically allows Curry to link it with the "natural" in natural philosophy, as we can see here. For the four canonical types of astrological practice, see Burnett, "Astrology," in Medieval Latin: An Introduction and Bibliographical Guide, F.A.C. Mantello and A.G. Rigg (eds), (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1996), 369–82, and the excursus on practical astrology in the overall introduction to my volume I, lxxix–lxxxiv.

[23] See my "Is Astrology a Type of Divination?: Thomas Aquinas, the Index of Prohibited Books and the Construction of a Legitimate Astrology in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance," International Journal of Divination and Prognostication 1 (2019): 36–74, and Chap. 5 of my vol. I

[24] For Roger Bacon's fundamental distinction between ‘astronomia iudiciaria et operativa', see pp. 119–20 of my volume I, which I will not discuss further here.

[25] For Chambers and his Cyclopedia, see my "Astrology," 558 f.

[26] We can see this in Marsilio Ficino's vastly influential De vita libri tres, in which, as a proper Neoplatonist, he integrates Aristotelian natural philosophy with Platonic and Neoplatonic metaphysics. See my "The Physics and Metaphysics of Talismans (Imagines Astronomicae): A Case Study in (Neo)Platonism, Aristotelianism and the Esoteric Tradition," in Platonismus und Esoterik in Byzantinischem Mittelalter und Italienischer Renaissance, Helmut Seng (ed), (Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag Winter, 2013), 149–73, and now my "Dancing with the Stars: A Preliminary Exploration as to Whether the Astrology in Ficino's De vita is Theurgical," in "Marsilio Ficino's Cosmology: Sources and Reception," edited by H Darrel Rutkin and Denis J.-J. Robichaud, Bruniana & Campanelliana 26 (2020/2): 403–19.

[27] Giovanni Pico della Mirandola also drew on this precise distinction in his influential Disputationes adversus astrologiam divinatricem; see my "Optimus Malorum: Giovanni Pico della Mirandola's Complex and Highly Interested Use of Ptolemy in the Disputationes adversus astrologiam divinatricem (1496), A Preliminary Survey," in Ptolemy's Science of the Stars in the Middle Ages, David Juste, Benno van Dalen, Dag Nikolaus Hasse and Charles Burnett, Turnhout: Brepols (Ptolemaeus Arabus et Latinus – Studies 1), 2020, 387–406. For the text of Pico's Disputations, see now Benjamin Topp's PhD thesis with a critical edition, German translation and extensive introduction of the Proem through Book 4. He also argues (inconclusively to my lights) that the title should Disputations against the Astrologers (Disputationes adversus astrologos), 50–52. For a valuable study of Pico's Disputations and its influence, primarily in the Low Countries, see Steven Vanden Broecke, The Limits of Influence: Pico, Louvain and the Crisis of Renaissance Astrology (Leiden: Brill, 2003). For a more problematic approach to Pico and his influence, see Ovanes Akopyan, Debating the Stars in the Italian Renaissance: Giovanni Pico della Mirandola's Disputationes adversus astrologiam divinatrice and its reception (Leiden: Brill, 2021).

[28] See Alessandra Tarabochia Canavero, "Il De triplici vita di Marsilio Ficino: Una strana vicenda ermeneutica," Rivista di Filosofia Neoscolastica 69 (1977): 697–717.

[29] The problems with this highly rhetorical description of what judicial astrologers do are significant, but I cannot go into them here.

[30] Aristotle was also taught in England at least through the middle of the 17th century, as we can see in the case of Isaac Newton himself, whom we know began his studies at Trinity College, Cambridge in 1661 by reading Aristotle before moving on to study Descartes. See Isaac Newton, Certain Philosophical Questions: Newton's Trinity Notebooks, J.E. McGuire and Martin Tamny (eds), (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983).

[31] Simon Schaffer, "Newton's Comets and the Transformation of Astrology."

[32] See my "‘Why Newton Rejected Astrology: A Reconstruction' or ‘Newton's Comets and the Transformation of Astrology: 20 Years Later,'" Cronos: Cuadernos Valencianos de Historia de la Medicina y de la Ciencia 9 (2006): 85–98.

[33] See Sarah J. Schechner, Comets, Popular Culture, and the Birth of Modern Cosmology (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999).

[34] This provides the structure for the second half of his book.

[35] This was especially the case in the 18th and 19th centuries with the increasingly popular almanac Old Moore, which also provided a broad range of popular scientific education for which the almanacs are rightly praised.

[36] Curry's follow up to Prophecy and Power valuably takes the story throughout the 19th century; A Confusion of Prophets: Victorian and Edwardian Astrology (London: Collins and Brown, 1992).

[37] This Foreword was composed as part of a project that has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (GA n. 725883 EarlyModernCosmology).