Horary Astrology and the Devotion to St. Anthony of Padua

Two Sacred Arts in Parallel

Abstract

This article examines two sacred traditions for recovering lost objects: the celestial art of horary astrology, transmitted from Persian and Arabic sources through medieval Latin synthesis to William Lilly's seventeenth-century English formulation, and the devotional practice of invoking help from St. Anthony of Padua, patron saint of lost things. Both traditions arise from a shared understanding: that human beings exist within a meaningful, organized cosmos, and that the experience of loss—far from being merely inconvenient—occasions direct knowing about our participatory relationship with this larger order. The lost object becomes a teacher. The search becomes an act of connection. Whether through reading celestial configurations or through the focused intentionality of prayer, these practices expand consciousness beyond its ordinary locality, aligning it with the cosmic whole that holds all things in their places. This study presents both traditions as technologies of gnosis—ways of knowing that transcend ordinary spatiotemporal limitation and reveal the nature of the ensouled universe we inhabit. For the working astrologer, detailed technical instruction in classical horary methods is provided; for the contemplative practitioner, the prayer tradition is examined as a timeless technology of consciousness.

Introduction: The Gnosis of Loss

The experience of losing something valuable occasions a distinctive form of distress—but also, for those prepared to notice, a distinctive form of revelation. We find ourselves suddenly aware of the limits of our knowledge. We do not know where the object is. Our ordinary faculties of memory and reason have failed us. The familiar world, which moments ago seemed stable and navigable, has become strange. Something that should be here is not here. The cosmic order we had unconsciously assumed—the order in which our possessions remain where we put them—has been disturbed.

This disturbance is the beginning of gnosis, or wisdom. The lost object teaches us, first, that we had been assuming the primacy of an order we did not create and do not control. Our keys, our books, our precious items—we arranged them according to internal structures that mirror, imperfectly, the celestial order. The Byzantine corners of our minds are reflected in how we organize our spaces. When something goes missing, we encounter the gap between our local organization and the larger order that actually governs where things are. The search for the lost object becomes an attempt to reconnect with that larger order—to expand beyond the cramped locality of ordinary awareness into a participatory knowing of the whole.

Those with fixed signs on the angles of their natal charts often expect things to remain where they belong. The physical environment should reflect and sustain the internal sense of stability. When this expectation is violated, the disturbance is not merely practical but cosmological. The psyche responds with default reactions: someone must have stolen it; We definitely put it there; the world has become unreliable. These reactions defend against the deeper recognition that our sense of order was always partial, always local, always dependent upon a larger coherence we did not author.

Throughout human history, this common predicament has generated remarkably consistent responses: the appeal to sources of knowledge beyond ordinary cognition, the employment of structured practices that shift consciousness, the cultivation of receptive attention. These responses appear across cultures that had no contact with one another, suggesting that they arise from something fundamental about human nature and the meaningful cosmos we inhabit.

This study examines two such responses that developed in overlapping historical contexts: the horary astrologer's art, transmitted from the Abbāsid court through medieval Latin synthesis to William Lilly's seventeenth-century English practice, and the devotion to St. Anthony of Padua, patron saint of lost things. Both reveal that we are more intimately connected to everything—on physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual levels—than our default consciousness recognizes. Both demonstrate that the universe is organized, responsive, and accessible to those who approach it rightly.

Part One: The Humility of Not-Knowing

Both traditions begin from the same human situation: the seeker does not know where the lost object is, and ordinary means of discovery have failed. The very act of consulting an astrologer or praying to St. Anthony constitutes an acknowledgment that one's own faculties are insufficient. This is not weakness but wisdom—the recognition that we are not autonomous knowers but participants in a larger order that exceeds our grasp.

This posture of acknowledged limitation distinguishes both practices from purely technological approaches. The person who sincerely poses a horary question or offers a prayer is not merely activating a procedure but entering into a relationship with the cosmos, with the communion of saints, with something greater than the isolated self. The humility of not-knowing creates the opening through which assistance can flow.

The Horary Moment

In classical horary astrology, the moment of acknowledged limitation is cosmically significant. The chart is cast for the precise instant when the question is posed to the astrologer—not when the object was lost, not when the querent first noticed its absence, but when the question itself takes form in the presence of the interpreter. The Persian and Arabic astrologers who developed this art understood the moment of sincere questioning as a kind of birth: the question comes into being, and the heavens at that instant reflect its nature and outcome.[1]

This understanding rests on the ancient insight that the cosmos is not a dead mechanism but a living whole in which all things operate. The Hermetic axiom 'as above, so below' expresses not a technique but an ontology: the celestial and terrestrial realms correspond because they are aspects of a single ensouled reality. When a genuine question arises—born of real need, fundamental limitation, authentic desire to know—it occurs within this living cosmos, and the cosmos at that moment bears witness to it.

Māshāʾallāh ibn Atharī (c. 740–815), the Persian Jewish astrologer whose participation in selecting the auspicious moment for Baghdad's foundation in 762 CE attests to his prominence, established this principle in his works on masāʾil (interrogations).[2] The querent's uncertainty is not a defect to be overcome but a necessary condition: genuine not-knowing opens the moment for celestial testimony. A person who already knows where the object is cannot sincerely pose the question, and an insincere question—one that does not arise from authentic need—lacks the existential weight that makes the heavens speak.

This isn't manipulation; it's respectful engagement. The astrologer does not compel the stars to reveal anything. Instead, the sincere question, arising from genuine limitation, participates in the cosmic moment, and the skilled interpreter reads what is already written there.

The Prayer's Beginning

The devotional tradition understands this same movement of acknowledged limitation through the grammar of intercession. The devotee who turns to St. Anthony confesses not merely epistemic limitation but creaturely dependence—dependence on God, mediated through the communion of saints. Prayer presupposes that the one praying cannot accomplish the desired end through their own power.[3]

The formal prayers to Anthony make this explicit

O Holy Saint Anthony, gentlest of Saints, your love for God and charity for His creatures made you worthy, when on earth, to possess miraculous powers. Miracles waited on your word, which you were ever ready to speak at the request of those in trouble or anxiety.

The prayer begins by acknowledging what Anthony was and is—a saint whose miraculous powers derived from love and charity, whose intercession was available to 'those in trouble or anxiety.' The person praying identifies themselves as belonging to this category: troubled, anxious, in need of assistance beyond their own capacity. The popular rhyme compresses this acknowledgment to its essence:

Saint Anthony, Saint Anthony, please look around— Something is lost and cannot be found.

The final line states the situation with perfect simplicity: the object cannot be found—not merely has not been found, but exceeds the finder's present capacity. The devotee confesses limitation and asks the saint to supply what is lacking.

What unites these two beginnings—the horary question and the intercessory prayer—is not identical metaphysics but shared sacred anthropology. Both traditions recognize that the human being is not a self-sufficient knower but a creature embedded in larger orders of meaning that can be approached through appropriate forms. Both understand that the posture of sincere need, rather than constituting an embarrassing failure, activates a channel that proud self-sufficiency keeps closed, and in some instances will even 'kick open' the doors of perception.

The Parable of the Lost Sheep

The Gospel parable illuminates the posture these traditions cultivate. The shepherd who loses one sheep out of a hundred does not passively wait for it to return. The shepherd leaves the ninety-nine and searches with total commitment until the lost one is found. The parable emphasizes both the value of what is lost—significant enough to warrant leaving the rest—and the active, seeking quality of the search.

Neither horary astrology nor the Anthony devotion encourages passive waiting. Both mobilize the seeker's full engagement. The horary querent poses the question with genuine need; the devotee prays with focused intention. The practices do not replace searching but empower it—they connect the local search with the cosmic order that knows where the object is, allowing guidance to flow into awareness that might otherwise remain closed.

The Founding Legend

Anthony's patronage of lost things traces to a specific narrative of acknowledged limitation—one that models the posture the devotion invites. Fernando Martins de Bulhões, born in Lisbon around 1195, entered religious life as an Augustinian canon before transferring to the Franciscan Order in 1220, taking the name Anthony.[4] His exceptional memory and intellectual gifts made him one of the most celebrated preachers in medieval Europe—Pope Gregory IX called him the Arca Testamenti (Ark of the Testament) for his comprehensive scriptural knowledge.[5]

The legend establishing his patronage concerns a psalter—a book of psalms with his personal annotations, invaluable for his teaching and preaching.[6] A novice borrowed this book and then departed the friary without permission, taking the psalter with him. Anthony's ordinary means of recovery had failed. He prayed for the book's return. The novice, struck by a terrifying apparition, returned both himself and the psalter to the community.

The narrative establishes a pattern: something valuable is lost; ordinary means fail; prayer occasions recovery. But notice who models this pattern. Anthony himself—the great preacher, the Ark of the Testament—cannot by his own power recover his own book. He must pray. The founding legend does not present Anthony as a celestial retrieval service but as one who himself knew the humility of not-knowing and turned to a higher power.

This pattern crystallized in the medieval responsory:

Si quaeris miracula[7]

Cedunt mare, vincula; membra resque perditas petunt et accipiunt iuvenes et cani.

(The sea yields, chains fall; young and old seek and receive lost limbs and lost things.)

The phrase resque perditas—'and lost things'—embedded Anthony's patronage within a catalogue of greater miracles. The gradient from liturgical Latin to nursery rhyme parallels the democratization of astrological technique from Māshāʾallāh's technical Arabic to Lilly's accessible English. In both traditions, sophisticated arts became available to ordinary seekers through simplified forms that preserved essential function.

Part Two: The Persian and Arabic Foundations of Horary Astrology

The horary techniques transmitted to the Latin West derive primarily from the remarkable intellectual synthesis achieved at the Abbāsid court in Baghdad during the eighth and ninth centuries. Under the patronage of caliphs al-Manṣūr (r. 754–775) and Hārūn al-Rashīd (r. 786–809), scholars translated the astronomical and astrological heritage of multiple civilizations—Greek, Persian, Indian, and the remnants of Babylonian tradition—into Arabic, producing a sophisticated technical literature that would dominate astrological practice for centuries.

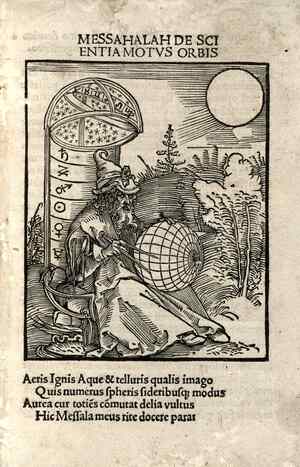

Māshāʾallāh ibn Atharī (c. 740–815)

Masha'allah with astrolabe, gazing at the sky in a richly illuminated manuscript page, 1468. (Wikimedia)

Māshāʾallāh ibn Atharī, a Persian Jewish astrologer working in Baghdad, stands as one of the founding figures of medieval horary practice. His participation in selecting the auspicious moment for the foundation of Baghdad in 762 CE demonstrates both his prominence and the integration of astrological consultation into the highest levels of governance.[1] His works on interrogations (masāʾil) established foundational principles upon which subsequent astrologers would elaborate.

For questions of lost objects, Māshāʾallāh established the basic significator system: the ruler of the Ascendant represents the querent (the person asking the question), while the ruler of the second house signifies movable possessions.[8] The Moon serves as universal co-significator, reflecting the querent's emotional state and providing additional testimony through her aspects and position. This tripartite structure—querent, object, and Moon—remains fundamental to horary practice.[9]

Māshāʾallāh also distinguished between items that are truly lost (whose location is unknown) and items that are mislaid (misplaced within one's own sphere). For mislaid items, the fourth house and its ruler gain significance, as this house represents one's home and immediate environment. This distinction matters practically: mislaid items typically require attention to immediate surroundings, while genuinely lost items may have left the querent's sphere of influence entirely.

Sahl ibn Bishr (fl. 815–825)

Sahl ibn Bishr, another astrologer at the ʿAbbāsid court, produced systematic treatises on interrogational astrology that achieved wide circulation. His Kitāb al-masāʾil (Book of Questions) provided detailed protocols for various categories of horary inquiry, including substantial material on lost objects.[9]

Sahl's major contribution was the systematic elaboration of takmīl—perfection or completion—as the technical criterion for determining whether a matter will come to fruition.[10] In horary astrology, perfection occurs when the significators of the relevant parties (here, querent and lost object) form an applying aspect that completes. The quality of this perfection depends on several factors: the type of aspect (conjunction and trine being most favorable, square and opposition more difficult), the essential dignities of the planets involved, and crucially, the presence or absence of reception.

Reception, in Sahl's treatment, occurs when a planet receives another into one of its dignities—domicile, exaltation, triplicity, term, or face.[11] When the significator of the lost object receives the significator of the querent, this indicates that the object is, metaphorically speaking, hospitable to being found—it 'welcomes' the querent's search. When the querent's significator receives the object's significator, the querent is well-disposed toward the object and motivated to recover it. Mutual reception, in which both planets receive each other, provides the strongest testimony of successful recovery.

Sahl also detailed alternative modes of perfection when the direct aspect between significators is absent.[12] Collection of light occurs when a third, slower planet receives aspects from both significators, gathering their light and bringing the matter to completion through a mediating agent. Translation of light occurs when a faster planet separates from one significator and applies to the other, carrying influence between them. In practical interpretation, these configurations often indicate that recovery will occur through a third party—someone who finds and returns the object, or an intermediary who facilitates its recovery.

Medieval Latin Transmission: Guido Bonatti

The Arabic astrological corpus entered Latin Europe through the translation movements of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, centered in Toledo, Sicily, and other contact zones between Islamic and Christian civilizations. These translations made available not only the technical manuals of Māshāʾallāh, Sahl, and their successors but also the philosophical framework within which Arabic astrologers understood their art.

Guido Bonatti (c. 1210–1296), an Italian astrologer who served various courts and military commanders, produced the Liber Astronomiae (Book of Astronomy, c. 1277), the most comprehensive astrological treatise written in Latin during the medieval period.[13] The work synthesizes Arabic sources with Bonatti's own extensive practical experience, providing detailed instruction on all branches of astrology.

Bonatti's treatment of lost objects appears in the fifth tractate, devoted to interrogations. He preserves and elaborates the Arabic significator system while adding distinctively medieval considerations. His famous 146 Considerations—preliminary conditions that must be assessed before judgment can proceed—include evaluation of the querent's sincerity, the fitness of the question to the moment, and various technical conditions that may impede or enable judgment.[14]

Bonatti's Method for Determining Location

Bonatti systematized the method of determining location through sign and house placement, a technique that later practitioners would further refine.[15] His approach combines elemental correspondence with house position to generate specific location judgments.

For elemental correspondence, fire signs (Aries, Leo, Sagittarius) indicate places associated with heat, height, and fire: upper stories, fireplaces, kitchens, forges, or areas receiving direct sunlight.[16] Earth signs (Taurus, Virgo, Capricorn) indicate low places, ground level, basements, gardens, agricultural areas, or places where goods are stored. Air signs (Gemini, Libra, Aquarius) suggest elevated locations with good light: upper rooms, places near windows, bookshelves, or areas associated with study and communication. Water signs (Cancer, Scorpio, Pisces) indicate damp or wet places: bathrooms, kitchens (near water), basements, laundry areas, or locations near bodies of water.

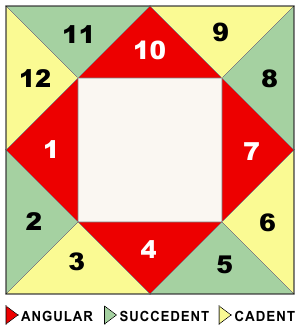

House position refines this elemental indication through angularity. Angular houses (1st, 4th, 7th, 10th) suggest the object is in a prominent, accessible location—often in plain sight or easily found once attention is directed there. Succedent houses (2nd, 5th, 8th, 11th) indicate intermediate accessibility: the object is present but somewhat concealed or requiring effort to locate. Cadent houses (3rd, 6th, 9th, 12th) suggest difficulty: the object may be distant, deeply hidden, or in an unexpected location.

Bonatti further refined location by noting the significance of cusp proximity.[17] A significator within approximately two degrees of a house cusp suggests liminal locations: doorways, windows, thresholds, edges of rooms, or transitional spaces. Planets in early degrees of signs (0–3°) may indicate objects in containers, boxes, or enclosed spaces; planets in late degrees (27–30°) suggest objects about to be moved or in transitional situations.

William Lilly and the English Synthesis

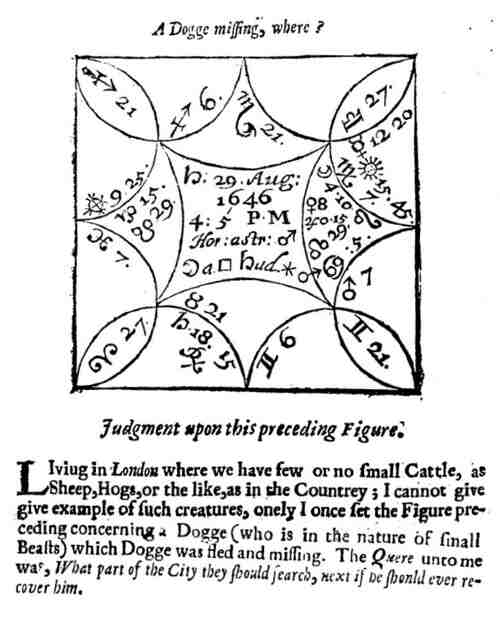

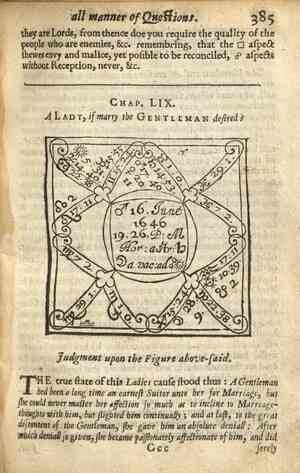

William Lilly (1602–1681) produced Christian Astrology (1647), the first comprehensive astrological textbook written in English.[18] Despite its title—chosen partly to deflect religious criticism in Puritan England—the work is primarily a technical manual synthesizing continental sources for English practitioners. Lilly's treatment of lost objects in Book II draws on Bonatti while incorporating his own extensive experience as a consulting astrologer in London.

Lilly's Refinements

Lilly preserved the Arabic-Latin framework while adding empirical observations derived from his practice.[19] His treatment of the Moon's role is particularly sophisticated. He notes that the Moon's separating aspects reveal the recent past—who last had the object, how it came to be lost—while her applying aspects indicate the unfolding future and the likely conditions of recovery.

On the critical condition of void of course—when the Moon makes no further aspects before leaving her current sign—Lilly provides nuanced judgment.[20] While void of course traditionally denies the matter (nothing will come of the question), Lilly notes exceptions: when the Moon is in Cancer (her domicile), Taurus (her exaltation), or Sagittarius and Pisces (where she has triplicity), her condition is less impaired. Similarly, if the Moon applies to the cusp of an angular house before leaving the sign, this may produce results despite the technical void.

Lilly also elaborated the directional correspondences of the signs, allowing the astrologer to advise the querent which direction to search:[21]

| Element | General Direction | Sign | Specific Direction |

|---|---|---|---|

| FIRE | East | Aries | Directly East |

| Leo | East-North-East | ||

| Sagittarius | East-South-East | ||

| EARTH | South | Taurus | Directly South |

| Virgo | South-East-South | ||

| Capricorn | South-West-South | ||

| AIR | West | Gemini | Directly West |

| Libra | West-North-West | ||

| Aquarius | West-South-West | ||

| WATER | North | Cancer | Directly North |

| Scorpio | North-East-North | ||

| Pisces | North-West-North |

Part Three: A Comprehensive Method for Finding Lost Objects

The following section synthesizes the methods of Māshāʾallāh, Sahl, Bonatti, and Lilly into a practical protocol for horary judgment regarding lost objects. This represents the classical tradition as received by working astrologers; individual practitioners may modify these methods according to their experience and the specific circumstances of each case.

Step 1: Establishing Significators

The ruler of the Ascendant signifies the Querent. This planet represents the person asking the question—their condition, resources, and capacity to recover the lost item. The Moon serves as a co-significator of the querent, reflecting their emotional state and providing additional information through its aspects and house position.

The ruler of the second house signifies the Lost Object for movable possessions generally. However, specific categories of objects may take different houses. The second house governs money, jewelry, portable valuables, and personal effects. The third house governs letters, documents, communication devices, and vehicles used for short journeys. The fourth house governs items mislaid within the home, property deeds, and family heirlooms. The fifth house governs items related to children, pleasure, creative work, and gambling. The sixth house governs tools, work equipment, items related to servants or employees, and small animals. The twelfth house governs large animals and items lost through self-undoing or hidden enemies.

The astrologer must exercise judgment in assigning the appropriate house. The Moon, regardless of which house signifies the object, always provides additional testimony about the item's condition and the likelihood of recovery.

Step 2: Assessing Whether the Object Will Be Found

Perfection (takmīl) provides the primary testimony for recovery. Examine whether the significators of querent and object will perfect an aspect.

Direct application: If the significator of the object applies to aspect the significator of the querent (or vice versa), and the aspect will perfect before either planet changes sign, this indicates recovery. As stated, conjunction and trine are most favorable; sextile is positive but may require effort; square indicates recovery with difficulty; opposition suggests recovery but with complications or disappointment.

Reception: The quality of reception significantly modifies the testimony. If the applying planet is received into the dignity of the receiving planet—especially into domicile or exaltation—recovery is strongly favored. Mutual reception between the significators provides excellent testimony. Lack of reception weakens perfection; reception in minor dignities (triplicity, term, face) provides moderate support.

Collection of light: If a slower-moving planet receives applications from both significators, a third party will bring about recovery. Identify this planet by house position to determine who: a family member (4th), friend (11th), colleague (7th), etc.

Translation of light: If a faster planet separates from one significator and applies to the other, this planet translates influence between them and describes the agent of recovery.

Negative testimonies include: significators separating rather than applying; the Moon void of course (making no further aspects before leaving her sign); both luminaries below the horizon and afflicted; the significator of the object in a cadent house, especially the 12th; the significator of the object combust (within 8°30' of the Sun); malefics (Mars, Saturn) afflicting the significator of the object without reception.

Step 3: Determining Location

If the testimonies favor recovery, the astrologer proceeds to determine where the object lies. This judgment combines multiple factors.

Sign of the significator indicates the elemental nature of the location. Fire signs (Aries, Leo, Sagittarius) indicate places near heat sources, fireplaces, kitchens, upper floors, places receiving direct sunlight, and workshops with fire. Earth signs (Taurus, Virgo, Capricorn) indicate ground level, basements, gardens, storage areas, places where goods are kept, agricultural areas, and under flooring. Air signs (Gemini, Libra, Aquarius) indicate upper rooms, near windows, bookshelves, studies, places associated with communication or learning, and elevated positions. Water signs (Cancer, Scorpio, Pisces) indicate bathrooms, kitchens (near water), laundry areas, basements (if damp), near plumbing, and locations near bodies of water.

House placement indicates accessibility. See 'Bonatti's Methods for Determining Location' for basic guidelines.

| House | Locations |

|---|---|

| 1st | On the querent's person, in their immediate vicinity, or where they recently were |

| 2nd | Among valuables, in a safe or lockbox for precious items |

| 3rd | In a vehicle, near communication equipment, with siblings or neighbors |

| 4th | In the home, the basement, with a family member, or in the garden |

| 5th | In recreation areas, with children, in a creative workspace |

| 6th | In the workspace, with employees, in areas associated with routine tasks, with small pets |

| 7th | With a partner or spouse, with a known third party, in public places |

| 8th | Hidden, in shared spaces, in areas associated with transformation or elimination |

| 9th | Far from home, in educational or religious settings, during travel |

| 10th | At work, in public spaces, in an authority's possession |

| 11th | With friends, in group settings, in communal spaces |

| 12th | Deeply hidden, in institutions, in places of confinement, lost through self-undoing |

Of course, specific house significations add further detail. The 1st house suggests the object is on the querent's person, in their immediate vicinity, or where they recently were. The 2nd house indicates, among valuables, a safe or lockbox for precious items. The 3rd house indicates a vehicle, near communication equipment, with siblings or neighbors.

The 4th house indicates the home, the basement, with a family member, or in the garden. The 5th house indicates recreation areas, with children, and in a creative workspace. The 6th house indicates the workspace, with employees, in areas associated with routine tasks, and with small pets.

The 7th house indicates a partner or spouse, with a known third party, in public places. The 8th house indicates hidden, in shared spaces, in areas associated with transformation or elimination. The 9th house indicates far from home, in educational or religious settings, during travel.

The 10th house indicates work, in public spaces, in an authority's possession. The 11th house indicates friends, group settings, and communal spaces. The 12th house indicates deeply hidden, in institutions, in places of confinement, lost through self-undoing.

As noted, the degree position also provides additional refinement. See 'Bonatti's Methods for Determining Location' for basic guidelines.

Step 4: Timing

The timing of recovery may be estimated from the degrees separating the significators from perfection, combined with the nature of the signs and houses involved. Cardinal signs (Aries, Cancer, Libra, Capricorn) and angular houses suggest days. Fixed signs (Taurus, Leo, Scorpio, Aquarius) and succedent houses suggest weeks. Mutable signs (Gemini, Virgo, Sagittarius, Pisces) and cadent houses suggest months.

The number of degrees between the significators provides the number of time units. Thus, if the object's significator applies to the querent's significator by trine, with 5 degrees separating them, and both are in cardinal signs with the object in an angular house, recovery might be expected in approximately 5 days.

Lilly notes that these timing principles require empirical adjustment based on the circumstances of the question and the astrologer's experience.21 Timing is among the most challenging aspects of horary judgment, and even experienced practitioners exercise considerable caution in making precise predictions.

Step 5: Additional Considerations

Theft versus loss: If the significator of the object is in the seventh house, or if the ruler of the seventh house afflicts the object's significator, theft may be indicated. The seventh house represents 'open enemies' and known third parties; the twelfth represents hidden enemies and those who work in secret. The peregrine planet (a planet in none of its dignities) nearest the Ascendant or Moon is a traditional significator of the thief.

Condition of the object: The essential dignity of the object's significator may indicate its current state. A well-dignified significator suggests the object is intact and in good condition; a debilitated significator may indicate damage, deterioration, or partial loss. Affliction from malefics without reception suggests harm to the object.

The Moon's testimony: Even when other significators are examined, the Moon's separating and applying aspects provide a narrative of the matter. Her separating aspect shows what has recently occurred (who last had the object, how it came to be lost); her applying aspects show what will unfold. An afflicted Moon often reflects the querent's emotional distress as much as objective conditions.

Bonatti's considerations: Before proceeding with judgment, the astrologer should assess whether the chart is radical—fit to be judged.[22] Traditional considerations include: whether the Ascendant is in very early or very late degrees (suggesting the question is premature or too late); whether the Moon is in the via combusta (15° Libra to 15° Scorpio, traditionally considered debilitating); whether the seventh house cusp or its ruler is afflicted (potentially compromising the astrologer's judgment); and whether the querent seems sincere in their question.

Part Four: The Prayer Practice

The devotion to St. Anthony operates through a different grammar but toward the same end: connection with the larger order that holds all things in their places. Understanding the prayer as a technology of consciousness illuminates how it works upon the practitioner.

The Oral Tradition

The formal liturgical prayers gave rise to simplified forms transmitted orally across generations. One such form, received through oral tradition:

Dear St. Anthony, please come round—

Something is lost and it needs to be found.

This is recited three times, invoking the power of threefold repetition that appears across many sacred traditions. The practitioner names the specific object, visualizes it clearly, and then—crucially—releases attachment to the outcome, sometimes focusing their awareness upon the heart center as they do so.

The release is essential as anxious grasping keeps consciousness contracted, fixated on the problem rather than open to solution. Release, on the other hand, allows expansion into the larger order where finding becomes possible. You cannot connect to the cosmos while clutching.

The threefold repetition hones intention. Naming the object precisely locates the search within consciousness. Visualization engages the imaginal faculty that bridges ordinary awareness and more profound knowing. Release shifts the psyche from contraction to receptivity. The entire sequence moves the practitioner from anxious locality into alignment with the cosmic order.

The saint, in this understanding, functions not as an external agent who finds the object for us but as a focusing device—a way of organizing intention and connecting with the sacred dimension of reality. The formal prayers preserve this technology while clothing it in intercessory language:

O Holy Saint Anthony, gentlest of Saints, your love for God and charity for His creatures made you worthy, when on earth, to possess miraculous powers. Miracles waited on your word, which you were ever ready to speak at the request of those in trouble or anxiety. Encouraged by this thought, I implore you to obtain for me the recovery of [name the item]. If the loss of this item is for the greater glory of God, and the spiritual welfare of my soul, please intercede for me.

The conditional clause—'If the loss of this item is for the greater glory of God'—acknowledges that the desired outcome may not align with larger purposes. This subordination to divine wisdom keeps the practice from becoming mere technique, preserving its sacred character. 'May this or something better come to pass'.

Part Five: Reading and Receiving

Here the traditions employ their most distinctive procedures, yet a structural parallel remains. In neither case does the seeker access knowledge directly; both require mediation through established forms. The astrologer consults the chart—a representation of celestial configurations at the moment of the question—and interprets its symbolism according to traditional rules. The devotee addresses a saint who participates in divine love on their behalf. Neither claims immediate, unmediated access to the knowledge sought—both practice forms of receptive attention.

Reading the Heavens

The astrologer's interpretive task proceeds through distinct stages: determining whether recovery is likely; identifying where the object lies; and estimating when it will be found. Each stage uses principles passed down from the original masters, as detailed in Part Three above. The process requires not merely calculation but attunement—the astrologer connects with the larger order and translates its testimony into practical guidance.

The celestial grammar emphasizes structure: houses, signs, aspects, dignities, and receptions. The cosmos is organized according to patterns the tradition has learned to read across millennia of observation and transmission. This organization is not separate from meaning but is meaning—the very structure of significance within which all things exist.

Awaiting Intercession

The devotional tradition involves no comparable interpretive procedure. The devotee prays and then waits. Or continues searching, but now with confidence that assistance has been invoked. The 'answer' to the prayer is not a set of instructions but the recovery itself, or its non-occurrence.

This difference is real but should not be overstated. The astrologer also waits—the chart provides guidance, but the querent must still search, and the outcome remains uncertain until the object is found or definitively lost. Both traditions place the seeker in a posture of receptivity, having done what can be done, now attending to what emerges.

Anecdotal testimony from devotees often describes a sense of being 'led' to the object: a sudden inclination to look in an unexpected place, a memory surfacing, an intuition. The tradition does not provide a mechanism for this; it simply notes that it occurs. Similarly, astrologers sometimes report that the act of casting and studying the chart seems to clarify the querent's own memory or intuition, as if the structured attention itself opens channels that were blocked by anxiety.

Both forms of receptive attention—interpretive reading and prayerful waiting—involve a similar underlying posture: having acknowledged limitation and employed proper procedure, the seeker attends to what comes, neither grasping nor abandoning hope. This is the posture of the supplicant before the sacred, and it appears across traditions that otherwise differ significantly in their theological grammar.

Part Six: Connection and Findability

A question arises within both traditions: does the degree of connection to a lost object affect the likelihood of its recovery? The person who loses a grandmother's ring may search with different intensity than the person who loses a generic pen. But is there more than psychology at work? Does the sentimental, symbolic, or spiritual connection to an object create channels through which guidance flows more readily?

The horary tradition offers tools for examining this question. The condition of the significators—their essential dignity, their reception by other planets, the aspects they form—may correlate with the nature of the querent's connection to the lost object. A strongly dignified significator of the lost thing might indicate an object of genuine value and significance; a peregrine significator might suggest something of less importance. The Moon, as co-significator of the querent's emotional state, reveals the intensity of concern.

More speculatively: reception between significators—where each planet welcomes the other into its dignities—might reflect a reciprocal relationship between seeker and sought. The object, in some sense, 'wants' to be found, just as the seeker wants to find it. This is not merely metaphorical if we understand the cosmos as ensouled and relational rather than mechanical and indifferent.

The devotional tradition gestures toward similar possibilities. The intensity of prayer, the clarity of visualization, the depth of the practitioner's connection to sacred reality—these seem to matter, not as magical manipulation but as degrees of alignment with the larger order. The grandmother's ring, carrying decades of symbolic weight, may be more deeply woven into the fabric of meaning that the practice accesses. The generic pen, barely registered in consciousness, offers less for the practice to work with.

This remains an area for further investigation rather than settled doctrine. What both traditions affirm is that connection is possible—that the apparently lost object has not fallen out of cosmic order but remains held within it, findable by those who expand beyond local limitation into participatory relationship with the whole.

Part Seven: Two Grammars of the Sacred

The parallels traced above are substantial. Both traditions understand the lost object as occasion for expanded knowing. Both employ structured practices that shift consciousness. Both presuppose an organized, responsive, ensouled cosmos. Both cultivate receptivity rather than grasping. Both accept that outcomes exceed human control while affirming that connection and guidance are possible.

Yet the traditions employ different grammars—different conceptual vocabularies, different ritual forms, other ways of articulating how the sacred operates. These differences merit acknowledgment, not to adjudicate between traditions but to honor each on its own terms.

The Celestial Grammar

Horary astrology reads the cosmos as text. The planetary positions and aspects at the moment of inquiry constitute a signature that the skilled interpreter deciphers. The heavens do not cause the object to be in a particular place; rather, the celestial configuration and the terrestrial situation participate in common meaning. 'As above, so below' expresses ontological correspondence, not mechanical causation.

This grammar is participatory: the querent's sincere question is itself a cosmic event, arising within and witnessed by the ensouled whole. The chart maps the situation as the cosmos holds it. Reading the chart is an act of attunement—the astrologer connects with the larger order and translates its testimony into practical guidance.

This cosmic grammar of celestial pattern recognition is not separate from meaning but rather is meaning—and the very epitome of the symbolic matrix in which all things exist.

The Intercessory Grammar

The Anthony devotion addresses a person: one who lived, died, and remains present within the communion of saints.[23] The grammar is relational in a distinctively personal sense—the devotee asks Anthony, Anthony participates in divine love, and assistance flows through this network of relationship.

Yet when understood as technology of consciousness—as the oral tradition suggests—the intercessory grammar converges with the celestial. The threefold prayer, the naming, the visualization, the release: these work upon the practitioner, shifting consciousness from contraction to expansion, from locality to connection. The saint becomes a focusing device, a way of organizing intention within a sacred relationship.

Convergence in Practice

Whether practitioners can speak both grammars simultaneously—casting horary charts and praying to St. Anthony for the same lost object—is a question each must answer for themselves. The traditions developed in contexts where such combinations were common; medieval Christians consulted astrologers and prayed to saints without evident sense of contradiction. Both were understood as ways of participating in the sacred order, not competing claims to exclusive truth.

What unites them is more fundamental than what distinguishes them: the recognition that we are not isolated knowers in a dead universe but participants in a living cosmos that responds to sincere approach. The lost object teaches this. The practices embody it. The finding—when it comes—confirms it.

Part Eight: Living with Uncertainty

Neither tradition promises certain results. This shared feature distinguishes both from magical thinking that demands outcomes and from technological approaches (like tracing a lost cell phone with an app) that guarantee results. Both traditions acknowledge that the sacred exceeds human control—and that this is appropriate.

The horary astrologer may judge that the object will not be found: the significators separate, the Moon is void, malefics afflict without reception. Or the chart may present contradictory testimonies, making a clear judgment impossible. Bonatti's 146 Considerations include conditions under which the astrologer should decline to judge entirely.[14] The tradition acknowledges its own limits.

The devotee prays without guarantee. The prayer's conditional dimension—'if this is for the greater glory of God'—acknowledges that the desired outcome may not align with larger purposes. Perhaps the loss serves some function the practitioner cannot perceive. Perhaps the object is meant to remain lost. The practice does not claim to override divine order but to participate in it.

This tolerance of uncertainty constitutes spiritual practice in itself. The seeker must act—pose the question, offer the prayer—without assurance. The object may never be found. The practice continues anyway. What is cultivated through repeated engagement with these traditions is not a success rate but a relationship: with the cosmos, with the sacred dimension of existence, with the reality that exceeds our grasp while remaining available to our participation.

The lost object, whether found or not, has already taught something: that our ordinary consciousness is local and limited; that there is a larger order we participate in but do not control; that practices exist for expanding beyond locality into connection; and that this expansion is itself valuable, regardless of whether the keys or the ring or the book come back to hand. Sometimes the lesson learnt is the simple act of surrender.

Conclusion: The Lost Object as Teacher

The experience of losing something valuable has occasioned remarkably recurrent human responses across diverse cultures and centuries. These responses appear so consistently that they illuminate something essential about human nature and the meaningful cosmos we inhabit.

Horary astrology and the devotion to St. Anthony represent two expressions of this perennial response. The horary methods transmitted from Māshāʾallāh and Sahl through Bonatti to Lilly constitute a sophisticated celestial art for mapping cosmic organization and locating lost things within it. The Anthony devotion, arising from the thirteenth-century hagiographic legend and transmitted through oral tradition and liturgical texts, offers a technology of consciousness that shifts the practitioner from anxious grasping to receptive connection.[24]

Both traditions understand the lost object as a teacher. The different grammars these traditions employ—celestial sympathy and saintly intercession—represent distinct articulations of how the sacred operates. Neither need be reduced to the other; neither need be adjudicated as correct while the other is dismissed. Both open onto the same underlying reality: an ensouled cosmos, organized and meaningful, that responds to a sincere approach.

The lost object, like the searcher, waits to be found. The traditions wait to be practiced. The practitioner who engages in them discovers not merely the location of misplaced keys but perhaps the nature of the universe itself (of which he is but a fractal portion): ordered, responsive, participatory, and conditional. The honest acknowledgement of the limitation of our awareness is the very condition for receiving what we cannot achieve on our own. Such is the gnosis of loss, then, and it remains available to all who are willing to commit fully to the search, bearing in mind that most ancient of maxims: 'seek and ye shall find'—YOURSELF!

William R. Morris, PhD, DAOM, RH

William Morris is a medical astrologer who gave his first consultation in 1977. He is practicing in the Kootenay Lake District of British Columbia. His background includes a master's degree in medical education from the University of Southern California, a clinical Doctorate and Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine, and a PhD in transformative inquiry focused on practice-based knowing. Will has published books on TCM and astrology and has 43 years of clinical experience using astrology as a feature of practice. During the 1990s he focused his practice on the methods of Lilly and Culpeper with 40 patients a week. He also used sidereal, cosmobiology, and Jyotish methods during that period. His work is a creole blend of music, astrology, medicine, and magic.

Scott Silverman

Scott Silverman is a consulting astrologer who currently resides in coastal Northeastern New England. He has been studying the symbolism and history of astrology since the mid-1980s and considers himself fortunate to have been one of the first students enrolled at Kepler College. His areas of extreme astrological interest include (but are not limited to) declination, Astrolocality, Uranian/Symmetrical, and Ancient Astrology. Scott is a long ago graduate of Vassar College and now wishes he had thought to major in Astronomy. He has edited a number of astrology books, as well as a series of special topic issues of NCGR Geocosmic Journal.

References

[1] Māshāʾallāh ibn Atharī, On Reception, trans. Benjamin N. Dykes (Minneapolis: Cazimi Press, 2010), 1–15.

[2] Māshāʾallāh, On Reception, 23–31.

[3] Virgilio Puhl, Saint Anthony: Doctor of the Gospel (Padua: Messaggero di sant'Antonio Editrice, 2003), 112–118.

[4] Luigi Gambero, Saint Anthony of Padua: His Life and Teaching (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1996), 23–45.

[5] Gambero, Saint Anthony, 67–72.

[6] Gambero, Saint Anthony, 156–167.

[7] Puhl, Saint Anthony, 145–156.

[8] Māshāʾallāh, On Reception, 45–67.

[9] Sahl ibn Bishr, The Introduction to the Science of the Judgement of the Stars, trans. Benjamin N. Dykes (Minneapolis: Cazimi Press, 2008), 45–78.

[10] Sahl ibn Bishr, Introduction, 89–112.

[11] Sahl ibn Bishr, Introduction, 113–128.

[12] Sahl ibn Bishr, Introduction, 134–156.

[13] Guido Bonatti, Liber Astronomiae, trans. Benjamin N. Dykes (Minneapolis: Cazimi Press, 2007), 567–623.

[14] Bonatti, Liber Astronomiae, 123–244.

[15] Bonatti, Liber Astronomiae, 245–312.

[16] Bonatti, Liber Astronomiae, 624–678.

[17] Bonatti, Liber Astronomiae, 679–695.

[18] William Lilly, Christian Astrology (London: Thomas Brudenell, 1647; reprint, Exeter: Regulus Publishing, 1985), 315–356.

[19] Lilly, Christian Astrology, 357–389.

[20] Lilly, Christian Astrology, 390–412.

[21] Lilly, Christian Astrology, 413–445.

[22] Bonatti, Liber Astronomiae, 696–745.

[23] Michael J. Scanlan, "St. Anthony of Padua: Evangelical Doctor," Franciscan Studies 54 (1997): 89–112.

[24] Gambero, Saint Anthony, 178–189.

Bibliography

Bonatti, Guido. Liber Astronomiae. Translated by Benjamin N. Dykes. Minneapolis: Cazimi Press, 2007.

Gambero, Luigi. Saint Anthony of Padua: His Life and Teaching. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1996.

Lilly, William. Christian Astrology. London: Thomas Brudenell, 1647. Reprint, Exeter: Regulus Publishing, 1985.

Māshāʾallāh ibn Atharī. On Reception. Translated by Benjamin N. Dykes. Minneapolis: Cazimi Press, 2010.

Puhl, Virgilio. Saint Anthony: Doctor of the Gospel. Padua: Messaggero di sant'Antonio Editrice, 2003, 112–156.

Sahl ibn Bishr. The Introduction to the Science of the Judgement of the Stars. Translated by Benjamin N. Dykes. Minneapolis: Cazimi Press, 2008.

Scanlan, Michael J. 'St. Anthony of Padua: Evangelical Doctor.' Franciscan Studies 54 (1997): 89–112.