Wild Yeast:

More Thoughts on the Abbasid Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement

DDimitri Gutas writes in Greek Thought, Arabic Culture, that “[t]he Graeco-Arabic translation movement is a very complex social phenomenon and no single circumstance or set of events can be singled out as its cause”[1]. He then proceeds to offer up sets of circumstances that were influential in creating what A.I. Sabra would term the 'local'[2] historical forces behind the 8th and 9th century translation movement. Gutas additionally discusses several factors which are not always given their due in brief accounts of the transmission of scientific knowledge from the Hellenized Roman Empire (East and West) to the Ancient Near East. My review of these factors will preface a consideration of the ideas that historians of Science George Saliba and A.I. Sabra propose as additional reasons of origin for the translation movement associated with the early Abbasid caliphates.

The Arab conquests of the 7th century resulted in the reunification of Egypt and Mesopotamia with Persia and India; they were now connected administratively, economically, and politically for the first time in well over a thousand years. Trade routes expanded and more amorphous borders led to the movement of raw materials, products, laborers, new technologies and skills, not to mention, in some cases, entire groups people across previously untenable cultural and regional divides.

Where goods and services travelled, so did ideas and new ways of thinking; commercial caravans carried as invisible cargo novel ideologies couched in language, thought and custom. It is especially worth noting that the Islamic reunification of the Ancient Near East, particularly East and West Mesopotamia, provided some much-needed breathing space for “certain Christian communities under Muslim rule and all other Hellenized people of the Islamic Commonwealth”[3] from the increasingly despotic Chalcedonian Orthodox Christians. The Nestorians and the Monophysites found refuge moving eastwards to regions that were both politically and geographically removed from the dogmatic decrees of the Chalcedonian Church. The Syriac speaking Nestorians, often Greek educated and fluent in Arabic, would prove to be key intermediaries in the transfer of knowledge from Greek to Arabic culture.

Gutas also believes that the agricultural revolution of 'pax Islamica'[4] during this period led to a greater overall prosperity for the Empire which, in turn, allowed it to accrue the necessary and considerable resources to sponsor a translation project of such magnitude. This agricultural revolution was partially the result of increased biodiversity as new crops (legumes, vegetables, and fruits) from Southwest Asia and the Eastern Mediterranean were introduced into both the fields and marketplaces of the more central regions of the empire. New agricultural methods as well, including those of 'intensive farming', were learnt from conquered populations.

The city of Samarqand was inhabited by one of these conquered and annexed populations. It just happened to be one of the centers of paper making in China. The city was defeated by Muslim armies in 704 CE and by the end of the 8th century Chinese paper makers had been installed in Baghdad and a paper mill built there[5]. According to historian Scott L. Montgomery “use of cheap locally produced paper, which entirely replaced papyrus and parchment before AD 900, allowed for more widespread duplication and distribution of existing manuscripts, thus bringing about a wider demand for scribal labor”[6]. So, one can credit Chinese prisoners of war, most decidedly a political factor, with providing another key ingredient of the translation movement: a far more affordable and durable medium on which to print text.

The paper making technology that Islam gained access to through the expansion of its empire assured that Arabic would become as Gutas asserts “the second classical language, even before Latin”[7]. There was a political dimension as well to the introduction of this new technology as “its use was championed and even dictated by the ruling elite…[and] various kinds of paper that were developed during that time bear the names of some powerful patrons of the translation movement”[8]. (Perhaps a more contemporary word for such patrons would be 'influencers'.)

Since early Islam was a theocracy, it is no simple task to distinguish the political from the religious incentives behind any particular element of the translation movement as they were often one and the same. Certainly, it was a desire to obtain greater knowledge, and therefore possible control, of the future that spurred the early Abbasid caliphates (and half a millennium before them, the early kings of the Sassanid-Persian empire) to seek whatever wisdom texts of al-mutaqaddimun (aka 'the ancients') they could lay their hands on. As Sabra notes, “the practical benefits promised by practitioners of medicine and astronomy and astrology and applied mathematics”[9] might be great enough to prompt any ruler to search out secular and scientific Greek texts on these subjects; indeed, an early Umayyad prince, Khalid ibn Yazid (before our story starts…) is known to have asked “one Stephen…in about A.D. 680”[10] to translate some Greek alchemical writings into Arabic.

Alchemical texts might offer the ambitious caliph the possibility of untold wealth (if one could only translate dross into gold, never mind the texts). Medical writings might tell one how to increase vigor and hold death at bay. But it was only astrological texts that which might tell one how to anticipate and comprehend events (the world year), how to order and understand time (the great cycles of planetary conjunctions pioneered by the Sassanids – which allowed later Arabic astrologers to postulate the end of the Abassid dynasty even as it bloomed), how to elect great cities (such as Baghdad) or even when to choose to fight a war (the military astrology of the Indians). The politics of empire expansion could thus be tempered by the timetables of Divine Will.

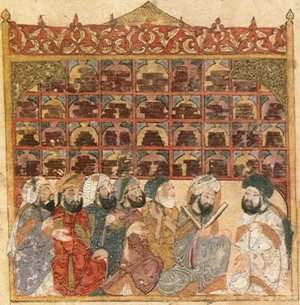

George Saliba refers to the 8th and 9th century translation movement as a 'still inexplicable”[11] phenomenon but thinks that one explanation of the “veritable explosion of interest in the 'foreign sciences'…in Baghdad”[12] might lie in “the technocratic and bureaucratic make up of the Umayyad and early Abassid times”[13]. His down-to-earth theory posits that “a tension between Arabs and the foreign civil servants who were still monopolizing the civic administration”[14] (and were probably Persian or Hellenized Syriacs) prompted “some private individuals, aspiring to greater administrative and social prestige for themselves or their protegees…[to] patronize translation activities”[15]. It seems a failure (rather than a leap) of the imagination to re-cast the Graeco-Arabic translation movement as the inadvertent love child of Muslim court intrigues. However, no leap of faith is needed to accept the fact that political, ethnic, philosophical, and even religious factions (say the scholars of hadith vs. the Mutazilites) were at variance with each other on a daily basis in Islam.

Both a smaller and larger purview of the factors behind the massive Graeco-Arabic translation movement is advanced by Sabra who views it as “the accomplishment of individuals who experienced the intersection, at a certain place and time of three major movements at work – namely, those of Hellenism, Arabism, and Islamism”[16]. He quotes historian R.W. Southern, who has elsewhere characterized “the process of acquisition and adaptation of Greek learning in Islam”[17] as “the most astonishing event in the history of thought”[18]. Sabra concurs that “[t]he event is astonishing because it is so unexpected”[19]. According to Sabra

the best way to explain the unexpected in history…insofar as it can be explained at all, is to try to understand it, not in terms of essences or spirits or inevitabilities, but as the outcome of choices made by individuals and groups responding to their situations as they understood them and perceived them”[20].

So, one is viewing history from a perspective of 'locality' (as opposed to the temporal 'non-locality' of the modern historian).

Sabra additionally speaks of “the way in which individuals aspect another culture as they direct their gaze to the other from their own location”[21](not unlike the planetos of Hellenistic astrology). What the aspecting individual actually perceives is determined by his own “interests, aspirations, and aptitudes and by the accessible aspects of the viewed culture”[22]. The unexpected in history, then, is affected both by how an individual aspects, or stands in respect to, another culture which is in turn shaped by mutual concerns of identity and accessibility.

Among the groups that Sabra catalogues as “pockets of Hellenistic learning … [which] ensured a certain continuity with the classical tradition”[23] are cultivated Persians, Christian doctors and theologians (no doubt from Jundishapur[24]), and pagan Sabians from Harran. They are each accorded their due influence in the translation movement but Sabra prefers to aggregate rather than isolate the historical essences of the movement: “to go beyond the availability of favorable conditions, and even beyond the minds of…Muslim patrons”[25] and contemplate “a new ideology with sweeping and universalist claims”[26].

This new ideology was that of the Islamic religion, exposed to both high impact collision and sustained “direct contact with a large variety of direct creeds (Jewish, Christian, Zoroastrian, Manichaean, etc.) …against which it had not merely to defend but – much more importantly – define itself, often in terms borrowed from its opponents”[27]. Sabra likens the result to

a huge intellectual ferment…of Islamic theology, philosophy, and science…fields of thought [which] represented the responses of so many groups of individuals to aspects of what was, in the context of religion and politics and power and the variety of competing ways to salvation, a very complex and lively intellectual atmosphere[28].

(by Janus Sandsgaard, Wikimedia)

In the context of such 'a huge intellectual ferment', the Graeco-Arabic translation movement emerges as a mighty percolation in the mash: an unexpected (but not necessarily shocking) reaction much like the occurrence of wild yeast in a bowl of sourdough starter. It is the leavening action of the wild yeast in the batter that allows the disparate ingredients, united[29], to rise as high as they may.

The Graeco-Arabic translation movement performed a similar function for the diverse peoples (Hellenized and non-Hellenized, Christian and Muslim, Arab and non-Arab, rural and cosmopolitan, Jews, Persians, Indians, and Asians) of the Islamic empire. This blending of multiple cultures in dynamic aspect was paralleled in the texts of the early translation movement; the Hellenistic scientific writings were in some cases being transmitted into Arabic from Sanskrit, Pahlavi or Syriac translations of Greek source texts. Thus, the translation movement can be thought of as a side-effect of a prolonged process of self-definition for the Islamic empire[30] through the action of cultural appropriation.

The act of cultural appropriation in this case was the procurement and, for the most part, successful attempt to literally transcribe and translate the Hellenistic texts; it is, after all, through literalist translation and the active reception of the transmission that a foreign text is absorbed, nativized[31] and rendered non-essential. However, it took the efforts of at least four civilizations to set the stage for the eventual nativization[32] of Greek astronomical and astrological texts into Arabic culture. Gutas meanwhile contends that the significance of the translation movement “lies in that it demonstrated for the first time in history that scientific and philosophical thought are international [and] not bound to a specific language and culture”[33]

Scott Silverman

Scott Silverman is a consulting astrologer who currently resides in coastal Northeastern New England. He has been studying the symbolism and history of astrology since the mid-1980s and considers himself fortunate to have been one of the first students enrolled at Kepler College. His areas of extreme astrological interest include (but are not limited to) declination, Astrolocality, Uranian/Symmetrical, and Ancient Astrology. Scott is a long ago graduate of Vassar College and now wishes he had thought to major in Astronomy. He has edited a number of astrology books, as well as a series of special topic issues of NCGR Geocosmic Journal.

References

[1]Dmitri Gutas, Greek Thought, Arabic Culture, (New York: Routledge, 1998), 7.

[2] Sabra proposes that “all history is local history – whether the locality is that of a short episode or of a long story”. See A.I. Sabra, “Situating Arabic Science: Locality Vs. Essence', Isis, vol. 87, 1996, 654 – 670.

[3] Gutas, 13.References

[4] Gutas, 12.

[5] Scott L. Montgomery, Science in Translation (Chicago, University of Chicago Press: 2001), 106.

[6] Ibid, 106.

[7] Gutas, 2.

[8] Gutas, 13.

[9] Sabra, 658.

[10] George Saliba, A History of Arabic Astronomy (New York, New York University Press: 1996), 52.

[11] Ibiid, 52.

[12] Ibid, 52.

[13] Ibid, 52.

[14] Ibid, 52.

[15] Ibid, 12.

[16] Sabra, 661.

[17] Ibid, 657.

[18] R.W. Southern, Western Views of Islam in the Middle Ages (Cambridge, MA: 1978), 8-9.

[19] Sabra, 657.

[20] Ibid, 657.

[21] Ibid, 658.

[22] Ibid, 658.

[23] Sabra, 658

[24] Variant spellings of this name may include Jandi Shapur, Gondishapur and Gundeshapur.

[25] Sabra, 685.

[26] Ibid, 658.

[27] Ibid, 658.

[28] Ibid, 658.

[29] According to Waybe Gisslen, author of Professional baking, 3rd edition, “[f]ermentation is the process by which yeast acts on sugars and changes them into carbon dioxide gas and alcohol. This release of gas produces a leavening action…[y]east is a microscopic plant that accomplishes the fermentation process by producing enzymes…[t[he following formula describes this reaction in chemical terms: C(6)H(12)O(6)> CO(2) + 2C(2)H(2)OH (Gisslen, 37). Gisslen also notes that “[a]n under fermented dough will not develop proper volume and the texture of the product will be coarse” (Gisslen, 53).

[30] See Sabra citation in note 26.

[31] See Montgomery, chapters 1 and 2, for a thorough discussion of this subject

[32] One may substitute the word ‘transmission' for ‘nativization'.

[33] Gutas, 192

Bibliography

Gisslen, Wayne, Professional Baking, 3rd edition. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc, 2001

Gutas, Dimitri, Greek Thought, Arabic Culture. New York: Routledge, 1998

Holden, James Hershel, A History of Horoscopic Astrology. Tempe, AZ: AFA, Inc, 1996

Lindberg, David L., Science in the Middle Ages. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978

Montgomery, Scott L., Science in Translation. Chicago: University of Chicago press, 2001

O'Leary, De Lacey, How Greek Science Passed to the Arabs. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, Ltd., 1949

Patterson, Gordon, The Essentials of Medieval History. Piscataway, NJ: Research and Education Association, 2001

Sabra, A.I., “Situating Arabic Science. Locality Vs, Essence”, Isis, vol.87, 654 – 70.

Saliba, George, A History of Arabic Astronomy. New York: ew York University Press, 1996

Southern, R.W., Western Views of Islam in the Middle Ages. Cambridge, MA: Havard University Press, 1978

Tester, Jim, 1987 A History of Western Astrology. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press,

Whitfield, Peter, Astrology. A History. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2001